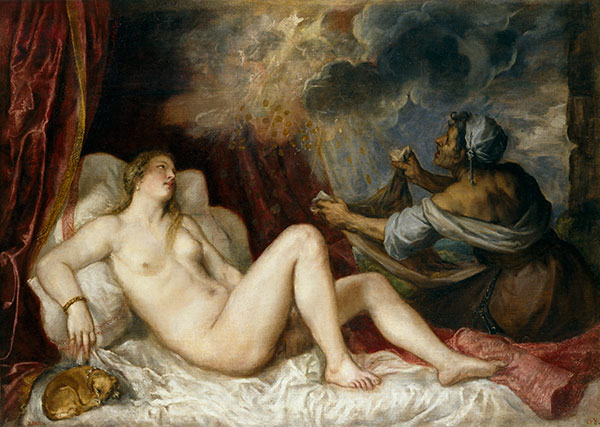

Titian, Diana and Callisto

1556-59Paintings sorted by Historical period | Painter | Subject matter | Pigments used

Related Paintings: Titian's Poesie Paintings

Titian painted a series of paintings with mythological subjects for King Philip II of Spain. Inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses, they are among Titian’s most admired works (1 and 2).

Quote from the website of DeYoung Museum San Francisco

“Titian and the Poesie

Among Titian’s most breathtaking works is a series of mythological subjects known as the poesie, which celebrate the loves of

ancient gods, goddesses, and mortals. In paintings of deep, sonorous color and broken, expressive brushwork, Titian created a visual

equivalent to lyric and emotive forms of poetry. The erotic beauty of the nude female form, often encompassed in the thick atmosphere of a pastoral landscape, is the focus of these compositions. Titian’s classical literary sources, especially the Metamorphoses, completed by the Roman author Ovid around AD 8, provide a veneer of respectability for these remarkable paintings. Ultimately, however, Titian’s poesie explore a world of physical sensuality that is made palpable through his brilliant technique. Designed for the pleasure of the male viewer, paintings such as Danaë were sought after by collectors and often replicated by the artist to satisfy the requests of noble patrons.”

The Poesie paintings

Danaë with a Nurse or Danaë Receiving the Golden Rain, 1553-54, Museo del Prado, Madrid

Danaë, ca 1554, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Russia

Danaë with Eros, 1544, Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples. Italy

Titian, Danaë with Nursemaid or Danaë Receiving the Golden Rain, 1560s. Museo del Prado

Venus and Adonis, 1554, The J. Paul Getty Museum

Venus and Adonis, 1554, Museo del Prado

Venus and Adonis, ca 1560, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Rome

Venus and Adonis, ca 1560, National Gallery of Art Washington

Venus and Adonis, ca 1554, National Gallery London

Titian, Venus and Adonis, 1555-60, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Diana and Actaeon, 1556-59, National Gallery London and National Galleries of Scotland

Titian, Diana and Actaeon, 1556-59, National Gallery London

Diana and Callisto, 1556-59, National Gallery London

Titian, Diana and Callisto, 1556-59, National Gallery London

Rape of Europa, 1559-62, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Titian, Rape of Europa, 1559-62, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Death of Actaeon, 1562, National Gallery London

Titian, Death of Actaeon, 1562, National Gallery London

Titian, Perseus and Andromeda, 1554-56, Wallace Collection London

Titian, Tarquin and Lucretia, 1568-71, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Titian, Tarquin and Lucretia, 1568-71, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

References

(1) Tanner, M, Sublime Truth and the Senses: Titian’s Poesi (Studies in Medieval and Early Renaissance Art History), Brepols N.V., 2019

(2) National Gallery London, Titian’s ‘poesie’ paintings. [Accessed 30 Jul. 2017].

Related Paintings: Interpretation of the Same Subject by Other Painters

Jan Brueghel the Elder, Diana and Callisto, ca 1608 (Jack S. Blanton Museum of Art, Austin Texas)

Peter Paul Rubens, Diana and Callisto, ca 1635 (Museo del Prado)

The Story of Diana and Callisto

Ovid, Metamorphoses Book II (A. S. Kline’s Version)

a

Bk II: 401-416 Jupiter sees Callisto

Now the all-powerful father of the gods circuits the vast walls of heaven and examines them to check if anything has been loosened by the violent fires. When he sees they are as solid and robust as ever he inspects the earth and the works of humankind. Arcadia above all is his greatest care. He restores her fountains and streams, that are still hardly daring to flow, gives grass to the bare earth, leaves to the trees, and makes the scorched forests grow green again.

Often, as he came and went, he would stop short at the sight of a girl from Nonacris, feeling the fire take in the very marrow of his bones. She was not one to spin soft wool or play with her hair. A clasp fastened her tunic, and a white ribbon held back her loose tresses. Dressed like this, with a spear or a bow in her hand, she was one of Diana’s companions. No nymph who roamed Maenalus was dearer to Trivia, goddess of the crossways, than she, Callisto, was. But no favour lasts long.

a

Bk II: 417-440 Jupiter rapes Callisto

The sun was high, just path the zenith, when she entered a grove that had been untouched through the years. Here she took her quiver from her shoulder, unstrung her curved bow, and lay down on the grass, her head resting on her painted quiver. Jupiter, seeing her there weary and unprotected, said ‘Here, surely, my wife will not see my cunning, or if she does find out it is, oh it is, worth a quarrel! Quickly he took on the face and dress of Diana, and said ‘Oh, girl who follows me, where in my domains have you been hunting?’

The virgin girl got up from the turf replying ‘Greetings, goddess greater than Jupiter: I say it even though he himself hears it.’ He did hear, and laughed, happy to be judged greater than himself, and gave her kisses unrestrainedly, and not those that virgins give. When she started to say which woods she had hunted he embraced and prevented her and not without committing a crime. Face to face with him, as far as a woman could, (I wish you had seen her Juno: you would have been kinder to her) she fought him, but how could a girl win, and who is more powerful than Jove? Victorious, Jupiter made for the furthest reaches of the sky: while to Callisto the grove was odious and the wood seemed knowing. As she retraced her steps she almost forgot her quiver and its arrows, and the bow she had left hanging.

François Boucher, ‘Jupiter and Callisto’ 1759

a

Bk II: 441-465 Diana discovers Callisto’s shame

Behold how Diana, with her band of huntresses, approaching from the heights of Maenalus, magnificent from the kill, spies her there, and seeing her calls out. At the shout she runs, afraid at first in case it is Jupiter disguised, but when she sees the other nymphs come forward she realises there is no trickery and joins their number. Alas! How hard it is not to show one’s guilt in one’s face! She can scarcely lift her eyes from the ground, not as she used to be, wedded to her goddess’s side or first of the whole company, but is silent and by her blushing shows signs of her shame at being attacked. Even if she were not herself virgin, Diana could sense her guilt in a thousand ways. They say all the nymphs could feel it.

Nine crescent moons had since grown full when the goddess faint from the chase in her brother’s hot sunlight found a cool grove out of which a murmuring stream ran, winding over fine sand. She loved the place and tested the water with her foot. Pleased with this too she said ‘Any witness is far away, let’s bathe our bodies naked in the flowing water.’ The Arcadian girl blushed: all of them took off their clothes: one of them tried to delay: hesitantly the tunic was removed and there her shame was revealed with her naked body. Terrified she tried to conceal her swollen belly. Diana cried ‘Go, far away from here: do not pollute the sacred fountain!’ and the Moon-goddess commanded her to leave her band of followers.

Gaetano Gandolfi Bologna, “Diana and Callisto”, 18th Century

a

Bk II: 466-495 Callisto turned into a bear

The great Thunderer’s wife had known about all this for a long time and had held back her severe punishment until the proper time. Now there was no reason to wait. The girl had given birth to a boy, Arcas, and that in itself enraged Juno. When she turned her angry eyes and mind to thought of him she cried out ‘Nothing more was needed, you adulteress, than your fertility, and your marking the insult to me by giving birth, making public my Jupiter’s crime. You’ll not carry this off safely. Now, insolent girl, I will take that shape away from you, that pleased you and my husband so much!’ At this, she clutched her in front by the hair of her forehead and pulled her face forwards onto the ground. Callisto stretched out her arms for mercy: those arms began to bristle with coarse black hairs: her hands arched over and changed into curved claws to serve as feet: and her face, that Jupiter had once praised, was disfigured by gaping jaws: and so that her prayers and words of entreaty might not attract him her power of speech was taken from her. An angry, threatening growl, harsh and terrifying, came from her throat. Still, her former feelings remained intact though she was now a bear. She showed her misery in continual groaning, raising such hands as she had left to the starry sky, feeling, though she could not speak it, Jupiter’s indifference. Ah, how often she wandered near the house and fields that had once been her home, not daring to sleep in the lonely woods! Ah, how often she was driven among the rocks by the baying hounds, and the huntress fled in fear from the hunters! Often she hid at the sight of wild beasts forgetting what she was, and though a bear she shuddered at the sight of other bears on the mountains and feared the wolves though her father Lycaon ran with them.

a

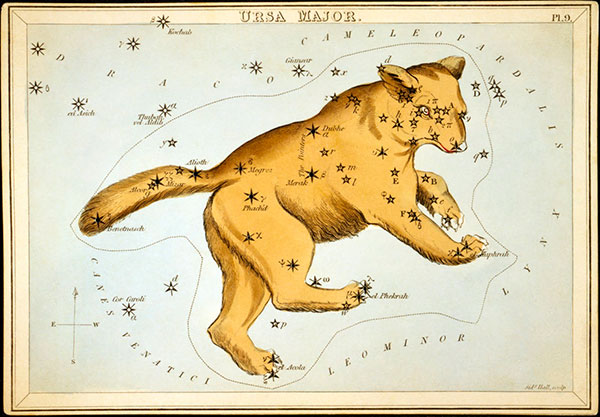

Bk II: 496-507 Arcas and Callisto become constellations

And now Arcas, grandson of Lycaon, had reached his fifteenth year ignorant of his parentage. While he was hunting wild animals, while he was finding suitable glades and penning up the Erymanthian groves with woven nets, he came across his mother, who stood still at sight of Arcas and appeared to know him. He shrank back from those unmoving eyes gazing at him so fixedly, uncertain what made him afraid, and when she quickly came nearer he was about to pierce her chest with his lethal spear.

Arcas and Callisto – Hendrik Goltzius (after Holland, Mülbracht) 1558-1617

a

All-powerful Jupiter restrained him and in the same moment removed them and the possibility of that wrong, and together, caught up through the void on the winds, he set them in the heavens and made them similar constellations, the Great and Little Bear.

The Constellation of the Great Bear (Ursa major)

Overview

Medium: Oil

Support: Canvas

Size: 187 x 204.5 cm

Art period: High Renaissance

National Gallery London and National Galleries of Scotland

Inventory number: NG6616

Titian, Diana and Callisto is a depiction of a dramatic story of deceit and shame. Jupiter seduces Callisto in the guise of a woman, whereupon Diana transforms her into a bear. This is one of the series of ‘poesie’ paintings with mythological subjects painted for King Philip II of Spain. Inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses, they are among Titian’s most admired works

Titian employed an extensively wide palette of nearly all pigments known in the Renaissance such as carmine cochineal, vermilion, red lead, natural ultramarine, smalt, verdigris, malachite, and lead-tin yellow.

Diana and Actaeon, Diana and Callisto, and The Death of Actaeon were hung together as part of the spectacular multi-arts project Metamorphosis: Titian 2012 staged jointly by the National Gallery London and the Royal Opera House.

Pigments

Pigment Analysis of Titian, Diana and Callisto

The following pigment analysis is based on the work of scientists at the National Gallery London (1).

1 Pink dress of the nymph behind Callisto: the lowest beige-coloured layer of lead white, black, and a little red ochre. The orange-brown layer above it contains yellow ochre and red ochre with some black. The top pale rose pink layer consists of lead white and carmine lake.

2 Deep green shrubs behind the Callisto group: verdigris mixed with varying amounts of yellow ochre.

3 Deep pink dress of the nymph to the right of Diana: The lowest orange-red layer consists of vermilion, red lead, and lead white. The next two pink layers consist of lead white, carmine lake, a little vermilion, and red lead. Further, there are several layers of carmine glaze with a small amount of lead white and black. Two different kinds of carmine can be found in this area of the painting. One is carmine produced from cochineal insects, the other is the so-called lacca de cimatura de grana – red pigment extracted from clippings (cimature) of a red textile containing carmine.

4 Blue dress of the nymph on the right: Lowest layer consists of carmine lake mixed with lead white and perhaps some vermilion. The top layer contains natural ultramarine.

5 Flesh paint on the shoulder of the nymph: Two pink layers of lead white with black and vermilion, and perhaps a little carmine lake.

6 Highlight of the purple drapery on which Diana is sitting: the top layer consists of lead white, ultramarine, and carmine lake. The next lower layer contains lead white, black, and a little red ochre.

7 Green in the foreground: lead-tin yellow and verdigris.

8 Orange-brown quiver: Layers of vermilion, red lead, lead white, and a little black.

9 Nymph’s hand: four layers consisting of lead white, vermilion, and yellow ochre with perhaps a little umber.

10 Blue landscape: lowest layer of smalt and lead white followed by a purple layer and two layers containing lead white, carmine lake, and a little vermilion. Two layers on top consist of natural ultramarine and lead white.

11 Yellow highlight of the curtain: The lower layer of yellow ochre with some lead white and a little black followed by a layer of orange-red ochre.

12 Tree branch in the upper-right edge: lower layer containing yellow ochre, lead white and black. The upper thick layer consists of malachite mixed with lead-tin yellow.

13 Green of the trees in the middle distance: verdigris mixed with varying amounts of yellow ochre and some malachite on top.

References

(1) Jill Dunkerton and Marika Spring. With contributions from Rachel Billinge, Helen Howard, Gabriella Macaro, Rachel Morrison, David Peggie, Ashok Roy, Lesley Stevenson and Nelly von Aderkas, Titian after 1540: Technique and Style in his Later Works, National Gallery Technical Bulletin 36, 2017, pp. 6-39. Catalog: Part 2 pp. 76-87. Jacqueline Ridge and Marika Spring, The Conservation History of Titian’s ‘Diana and Actaeon’ and ‘Diana and Callisto’ pp. 116-123 Notes and Bibliography pp. 124-136.

Pigments Used in This Painting

Resources

See the collection of online and offline resources such as books, articles, videos, and websites on Titian in the section ‘Resources on Painters‘

PowerPoint Presentations

Painter in Context: Titian

A richly illustrated presentation on the Venetian Renaissance painter Titian (Tiziano Vecellio) containing information on painting technique, pigments employed, and important written and online resources.

Number of slides: 23

Formats included in the download: PowerPoint Screen Presentation (ppsx) and pdf

Videos

Video: 'Titian, Diana and Callisto' by CNN

Video: 'Titian, Diana and Callisto' by National Gallery London

Video: 'Cochineal beetles in art | Titian’s ‘Diana and Callisto’' by National Gallery London

Video: 'Titian: Love, Desire, Death, by National Gallery London

Publications and Websites

Publications

(1) Jill Dunkerton and Marika Spring. With contributions from Rachel Billinge, Helen Howard, Gabriella Macaro, Rachel Morrison, David Peggie, Ashok Roy, Lesley Stevenson and Nelly von Aderkas, Titian after 1540: Technique and Style in his Later Works, National Gallery Technical Bulletin 36, 2017, pp. 6-39. Catalog: Part 2pp. 76-87. Jacqueline Ridge and Marika Spring, The Conservation History of Titian’s ‘Diana and Actaeon’ and ‘Diana and Callisto’ pp. 116-123 Notes and Bibliography pp. 124-136.

(2) Lawson, James. “Titian’s Diana Pictures: The Passing of an Epoch” Artibus Et Historiae, vol. 25, no. 49, 2004, pp. 49–63. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1483747.

(3) Tanner, M, Sublime Truth and the Senses: Titian’s Poesi (Studies in Medieval and Early Renaissance Art History), Brepols N.V., 2019.

Websites

Titian’s ‘poesie’: The commission, National Gallery London