Ultramarine Natural

Inorganic pigmentComposition and Properties of Ultramarine natural

Ultramarine is a complex sodium silicate containing sulfur and aluminum with the chemical formula Na7Al6Si6O24S3. The intense and unique blue color is caused by the unpaired electron in the sulfur radical anions S3-.

It is chemically stable under normal conditions and is also resistant to high temperatures. The pigment is also resistant to alkaline solutions and can thus be employed in fresco, it is, however, unstable even in dilute acids and decomposes to yield hydrogen sulfide.

There are no known incompatibilities with other pigments.

Art Teachers' Materials

Richly illustrated presentation on the properties, preparation, identification and use of this pigment

Pigment

Painted swatch

Mineral lapis lazuli

Video: 'Story of Blue' by Nature

Collection of 35 Ultramarine Pigments by Kremer Pigments

Names

Alternative names

Azzurrum ultramarinum, lapis lazuli ultramarine

Color Index

PB 29, CI 77007

Word origin

From Medieval Latin ultramarinus, literally “beyond the sea,” from ultra– “beyond” + marinus “of the sea”. Said to be so called because the mineral was imported from Asia.

From WordFinder

Ultramarin

German

Outremer

French

Oltremare

Italian

Ultramar

Spanish

References

Guido Frison and Giulia Brun, Lapis Lazuli, Lazurite, Ultramarine ‘Blue’, and the Colour Term ‘Azure’ up to the 13th Century, Journal of the International Colour Association 16 (2016), pp. 41-55.

Preparation of Ultramarine natural

The source of natural ultramarine is the mineral lapis lazuli which is a fairly complex mixture of limestone, silicate minerals and also pyrite containing the mineral lazurite which is the actual source of ultramarine.

The best known historical method for preparation of high-quality ultramarine from Lapis lazuli was described by the Italian painter Cennino Cennini in his well-known handbook for painters “Libro dell’arte o trattato della pittura” (1).

English translation of the original text by Cennino Cennini

“First take some lapis lazuli; and if you would know how to distinguish the best stones, take those which contain most of the blue colour, for it is mixed with what is like ashes. That which contains least of this ash pigment is the best; but be careful that you

do not mistake for it azzurro della magna, which is as beautiful to the eye as enamel.

Pound it in a covered bronze mortar, that the powder may not fly away; then put it on your slab porphyry, and grind it without water; afterwards, take a covered strainer like that used by the druggists for sifting drugs (spices), and sift it and pound again as much as is required. But bear in mind that though the more you grind, the more finely powdered the azzurro will be, yet it will not be so beautiful and rich and deep in colour; and that the finely ground sort is fit for miniature-painters, and for draperies inclining to white.

When the powder is prepared, procure from the druggist, six ounces of resin of the pine, three ounces of mastic, and three ounces of new wax to each pound of lapis lazuli. Put all these ingredients into a new pipkin and melt them together. Then take a piece of white linen and strain these things into a glazed basin.

Then take a pound of the powder of lapis lazuli; mix it all well together into a paste, and that you may be able to handle the paste, take linseed oil, and keep your hands always well anointed with this oil. This paste must be kept at least three days and three nights, kneading it a little every day; and remember that you may keep it for fifteen days or a month, or as long as you please.

When you would extract the azure from the paste, proceed thus. Make two sticks of strong wood, neither too thick nor too thin, about a foot long; let them be well rounded at each end and well polished (smoothed). Then, your paste being in the glazed basin into which you first put it, add to it a porringerful of lye, moderately warm; and with these two sticks, one In each hand, turn and squeeze and knead the paste thoroughly, exactly in the manner that you would knead bread.

When you see that the lye is thoroughly blue, pour it put into a glazed basin; take the same quantity of fresh lye, pour it over the paste, and work it with the sticks as before. When this lye is very blue, pour it into another glazed basin, and continue to do so for several days, until the paste no longer tinges the lye.

Then throw it away, it is good for nothing. Range all the basins before you on a table in order, that is to say, the first, second, third, and fourth ; then beginning at the first, with your hand stir up the lye with the azure, which by its weight will have sunk to the bottom, and then you will know the depth of colour of the azure. Consider how many shades of the azure you will have, whether three, or four, or six, or what number you please, always remembering that the first- drawn extracts are the best, as the first basin is better than the second.”

Video: Preparation of natural ultramarine

© 2014 Attila Gazo (masterpigments.com)

References

(1) Cennino Cennini, Libro dell’arte o trattato della pittura, written about 1400. English translation: Cennino Cennini, The Craftsman’s Handbook: The Italian “Il libro dell’arte,” Daniel Varney Thompson, translator, Dover Publications, 1954, pp. 37-38.

Full text of the English translation by Christiana Harringham is available online in facsimile form at Internet Archive. The above quote is taken from this online text, pp. 47-51.

(2) Denninger, E. Die Herstellung von reinem, natürlichem Ultramarinblau aus Lapislazuli nach der Methode des Cennino Cennini, Maltechnik. 70, 1964, 2-5.

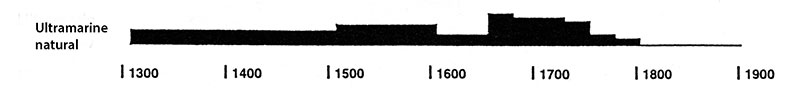

History of Use

The following graph gives the frequency of its use in the paintings of the Schack Collection in the Bavarian State Art Collections in Munich (1).

References

(1) Kühn, H., Die Pigmente in den Gemälden der Schack-Galerie, in: Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen (Ed.) Schack-Galerie (Gemäldekataloge Bd. II), München 1969.

(2) Mira S. de Roo, The Trade in Blue During the 17th Century: An Examination of Western European Pigment Trade in Azurite, Indigo, Lapis Lazuli, and Smalt During the 17th Century Through Works in the National Gallery, London, Master of Philosophy, University of Glasgow, 2004.

Examples of use

Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne, 1520-23

Sassoferrato, Virgin in Prayer, 1640-50

Johannes Vermeer, The Milkmaid, 1657-58

Video: 'Case Study 3.4: Ultramarine Blue in Two Paintings' by Dutton Institute

Identification

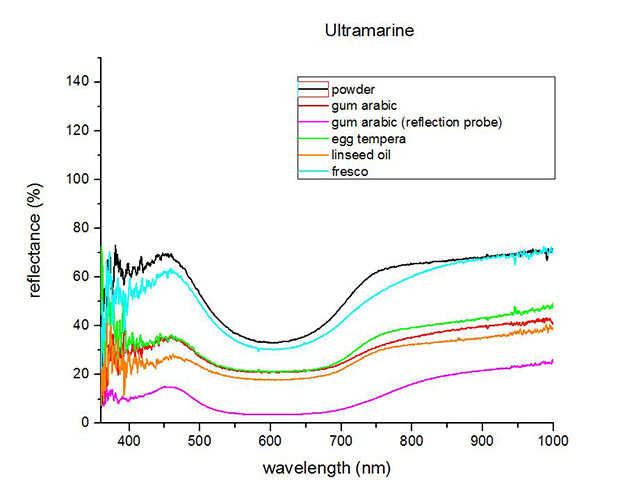

Fiber Optics Reflectance Spectrum (FORS)

Spectra by A. Cosentino, Cultural Heritage Science Open Source (CHSOS)

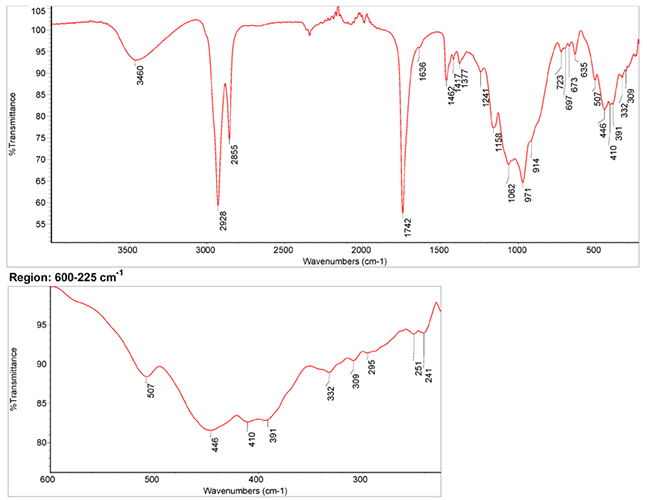

Infrared Spectrum

- Spectrum by S. Vahur, Database of ATR-IR spectra of materials related to paints and coatings, University of Tartu, Estonia

IR-Spectrum of lapis lazuli in linseed oil

2. IR-Spectrum of Lapis lazuli in the ATR-FT-IR spectra of different pure inorganic pigments, University of Tartu, Estonia

3. IR-Spectrum at National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST)

Raman Spectrum

Spectrum by Ian M. Bell, Robin J.H. Clark and Peter J. Gibbs, Raman Spectroscopic Library

University College of London

X-Ray Fluorescence Spektrum (XRF)

XRF Spectrum in the Free XRF Spectroscopy Database of Pigments Checker, CHSOS website.

References

(1) Osticioli, I., Mendes, N. F. C., Nevin, A., Gil, F. P. S. C., Becucci, M., & Castellucci, E. Analysis of natural and artificial ultramarine blue pigments using laser induced breakdown and pulsed Raman spectroscopy, statistical analysis and light microscopy. Spectrochimica Acta. Part A, Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 73(3), (2009) 525–31. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2008.11.028.

(2) De Torres, A. R., Ruiz-Moreno, S., López-Gil, A., Ferrer, P., & Chillón, M. C. Differentiation with Raman spectroscopy among several natural ultramarine blues and the synthetic ultramarine blue used by the Catalonian modernist painter Ramon Casas i Carbó. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy, (2014) n/a–n/a. doi:10.1002/jrs.4606.

(3) R.J.H. Clark, M.L. Franks, The resonance Raman spectrum of ultramarine blue, Chemical Physics Letters

Volume 34, Issue 1, 1 July 1975, Pages 69-72.

(4) M. Favaro, S. Bianchin, A. Guastoni, and F. Marini, Characterization of lapis lazuli and corresponding purified pigments for a provenance study of ultramarine pigments used in works of art, Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry-6-402 (2012).

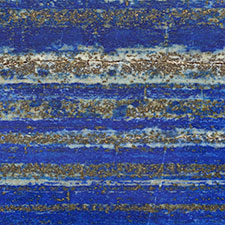

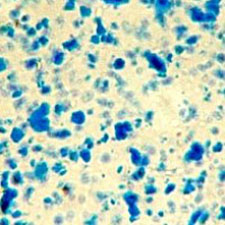

Microphotograph

image © Volker Emrath

Further Reading

References

(1) Kurella, A. und Strauss, I., Lapislazuli und natürliches Ultramarin, Maltechnik-Restauro, 1983, p. 34-54

(2) J. Plesters, Ultramarine Blue, Natural and Artificial, in Artists’ Pigments. A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, Vol. 2: A. Roy (Ed.) Oxford University Press 1993, p. 37-66. Available as pdf from the National Gallery of Art.

(3) , Sulfur in artwork: lapis lazuli and ultramarine pigments, Studies in Inorganic Chemistry (1984), Volume: 5, Sulfur, Pages: 67-89.

(4) A story of blue, Nature Video, 2014. Ashok Roy, National Gallery London, explains the story of natural ultramarine.

(5) Webexhibits, Pigments through the Ages, Ultramarine

(6) Philip Ball discusses the pigment Ultramarine, National Gallery London (Audio)

(7) S. Muntwyler, J. Lipscher, HP. Schneider, Das Farbenbuch, 2nd. Ed., 2023, alataverlag Elsau, pp. 50-53 and 422-431.

(8) Seel, F. et al. Das Geheimnis des Lapis Lazuli, Chemie in unserer Zeit, 8, 1974 p. 65.