Diego Velázquez, Apollo in the Forge of Vulcan

1629-30Diego Velázquez, Apollo in the Forge of Vulcan

1629-30Paintings sorted by Historical period | Painter | Subject matter | Pigments used

The Story

The original text by Ovid is quoted below. There is one noteworthy detail of the merged identities of the Greek god of Sun Helios and of Apollo, the god of poetry and music. In Homer’s original text it is Helios who informs Vulcan about his unfaithful wife, while Apollo appears only after the adulterers are caught in the net of the deceived husband (1).

Ovid, Metamorphoses Translated by A. S. Kline © 2004 All Rights Reserved

Book IV:167-189 Leuconoë’s story: Mars and Venus

Arsippe ceased. There was a short pause and then Leuconoë began to speak, while her sisters were quiet.

‘Love even takes Sol prisoner, who rules all the stars with his light. I will tell you about his amours.

He was the first god they say to see the adulteries of Venus and Mars: he sees all things first. He was sorry to witness the act, and he told her husband Vulcan, son of Juno, of this bedroom intrigue, and where the intrigue took place. Vulcan’s heart dropped, and he dropped in turn the craftsman’s work he held in his hand.

Immediately he began to file thin links of bronze, for a net, a snare that would deceive the eye. The finest spun threads, those the spider spins from the rafters, would not better his work. He made it so it would cling to the smallest movement, the lightest touch, and then artfully placed it over the bed.

When the wife and the adulterer had come together on the one couch, they were entangled together, surprised in the midst of their embraces, by the husband’s craft, and the new method of imprisonment he had prepared for them.

The Lemnian1, Vulcan, immediately flung open the ivory doors, and let in the gods. There the two lay shamefully bound together, and one of the gods, undismayed, prayed that he might be shamed like that. And the gods laughed. And for a long time it was the best-known story in all the heavens.’

————————————-

1) Lemnian: an inhabitant of the island of Lemnos in the north Aegean Sea

References

(1) Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez, Julián Gállego, Velázquez, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 01.01.1989, p. 113

Possible Source of Inspiration

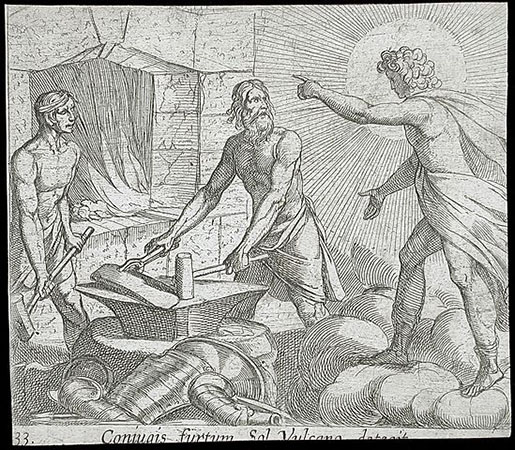

Velázquez created this painting during his stay in Rome possibly using the etching of the Italian artist Antonio Tempesta as inspiration.

Antonio Tempesta, Apollo in Vulcan’s Forge, 1606

Antonio Tempesta, Apollo in Vulcan’s Forge, 1606

Overview

Medium: Oil

Support: Canvas

Size: 223 cm × 290 cm

Art period: Baroque

Museo del Prado

Inventory number: P01171

Quote From an Exhibition Catalog

The following quotes are from the catalog of the Velázquez exhibition in the Metropolitan Museum of Arts in New York in 1989 and describe several interesting aspects of this painting.

“I believe that the influence of Guido Reni is undeniable in The Forge of

Vulcan – in the elegant friezelike composition, in the influence of ancient

sculpture, and in the palette, lighter and less robust than that of Joseph’s Coat

(the latter brings Guercino to mind). Especially delicate is the figure of the

young god Apollo, with his ephebic fairness and pearly flesh. His yellow

mantle and the aureole of rays about his head seem to illuminate the smithy’s

shadows. Heat and light radiate from the strip of red-hot metal that Vulcan is

working and from the fire in the furnace that outlines the bodies of two of the

surprised smiths. Vulcan and his workers stare at their visitor, hanging on his

every word-the young god’s presence and the gesture of his right hand

command attention. Velazquez has endowed this elegant and handsome youth

with a certain insolence not seen in the rather languid head (pl. 12) that is

often considered a study for this painting. Here the forceful Apollo tells the

lame Vulcan that the smith’s wife, Venus, has been unfaithful to him with

Mars, the god of war, for whom the pieces of (contemporary, not ancient)

armor are most likely being forged (some believe that the armor is destined

for Achilles).” (1)

“Velazquez’s choice of subject-a burlesque episode of the cuckolded

husband-is typical of the antimythological bent of Spanish artists and writers

of the Golden Age, but he gives this scene the same dignity he confers on all he

paints, whether it be a betrayed god or a dwarf. The Spanish attitude toward

mythological figures and episodes contrasts with the French stance of respectful

veneration, as seen in Louis Le Nain’s Venus at the Forge of Vulcan (Musee

Saint-Denis, Reims).” (2)

References

(1) and (2) Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez, Julián Gállego, Velázquez, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989, p. 113 and 114.

Pigments

Pigment Analysis

This pigment analysis is based on the book ‘Examining Velazquez’ (1). The availability and choice of pigments changed around 1600 and thus we perceive a notable difference between the paintings of the Renaissance such as Titian’s ‘Bacchus and Ariadne‘ and the ‘Apollo in the Forge of Vulcan’. Titian’s choice was pure pigments of high colour saturation, such as ultramarine, orpiment, or vermilion. Velázquez used lead-tin-yellow instead of Titian’s orpiment, azurite instead of ultramarine and red ochre instead of read lead or realgar.

Some colours in this painting also changed considerably with time. The best example is the originally green wreath of Apollo which is now of blue-green colour due to the degradation of the yellow lake mixed with blue azurite to obtain the desired green colour. Another example is the loincloths of the workers which are now rather flat and dull. The flesh colours painted with yellow ochre which does not change with time retained their lightness. This effect together with the darkening of the brown colours in the background brought about the unintended prominence of the semi-naked figures in the composition (1).

The blue-green colour of the shoelace of Apollo (Nr 1) was achieved by mixing azurite, yellow ochre, calcite, and red lake. The blue colour of the shoelace is a cool contrast to the orange robe.

The orange-brown robe of Apollo is painted with red lake, lead-tin-yellow, tin oxide, lead white, and calcite.

The paint in the foot of the man to the right of Vulcan (Nr 3) contains lead white, calcite, yellow ochre with possibly small amounts of red lake, bone black, azurite and vermilion.

The red-orange sheet of heated metal (Nr 4) is painted in vermilion, lead white and possibly a red lake, and calcite.

The gray-blue sky on the left (Nr 5) contains lead white, calcite, bone black, smalt, and possibly traces of yellow-brown ochre and natural ultramarine. The blue sky closer to Vulcan’s head (Nr 6) contains smalt, lead white, and possibly bone black, yellow ochre, and calcite.

The greenish-gray loincloth of the man on the far right (Nr 7) contains bone black, lead white, green earth, yellow ochre, calcite, and possibly small amounts of vermilion.

The blue-green wreath on Apollo’s head (Nr 8) is painted in azurite, yellow lake, lead white and yellow ochre. The yellow lake is not a very permanent pigment and its fading resulted in the bluish hue of the wreath.

Yellow-green loincloth of the man to the right of Vulcan (Nr 9) contains lead white, yellow ochre, calcite, azurite, and ochre.

References

(1) McKim-Smith, G., Andersen-Bergdoll, G., Newman, R. Examining Velazquez, Yale University Press, 1988, pp 115 – 119.

(2) P.C. Gutiérrez-Neiraa, F. Agulló-Ruedab, A. Climent-Fonta, C. Garrido, Raman spectroscopy analysis of pigments on Diego Velázquez paintings. Vibrational Spectroscopy, 69, 2013, 13 – 20.

(3) Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez, Julián Gállego, Velázquez, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989, pp. 113.

Pigments Used in This Painting

Resources

See the collection of online and offline resources such as books, articles, videos, and websites on Velázquez in the section ‘Resources on Painters‘

Videos

Video: 'Velázquez, Apollo in the Forge of Vulcan' by Smarthistory

Video: 'Velázquez, Apollo in the Forge of Vulcan' by Kyle Helvie

Publications and Websites

Publications

(1) McKim-Smith, G., Andersen-Bergdoll, G., Newman, R. Examining Velazquez, Yale University Press, 1988, pp 115 – 119.

(2) Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez, Julián Gállego, Velázquez, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989, pp. 110 – 115.