Diego Velázquez, The Surrender of Breda

1634-35Diego Velázquez, The Surrender of Breda

1634-35Paintings sorted by Historical period | Painter | Subject matter | Pigments used

Text by Théophile Gautier

From: Guide de l’Amateur au Musée du Louvre, Paris, 1882.

Included in Esther Singleton, Great Pictures as Seen and Described by Famous Writers, Dodd, Mead and Co., New York 1899.

The Surrender of Breda, better known under the name of Las Lanzas, mingles in the most exact proportion

realism and grandeur. Truth pushed to the point of portraiture does not diminish in the slightest degree the

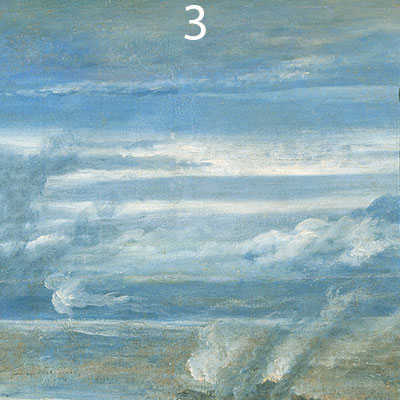

dignity of the historical style.A vast and spacious sky full of light and vapour, richly laid in with pure ultramarine, mingles its azure with

the blue distances of an immense landscape where sheets of water gleam with silver. Here and there

incendiary smoke ascends from the ground in fantastic wreaths and joins the clouds of the sky. In the

foreground on each side, a numerous group is massed: here the Flemish troops, there the Spanish troops,

leaving for the interview between the vanquished and victorious generals an open space which Velasquez has

made a luminous opening with a glimpse of the distance where the glitter of the regiments and standards is

indicated by a few masterly touches.The Marquis of Spinola, bareheaded with hat and staff of command in hand, in his black armour damascened

with gold, welcomes with a chivalrous courtesy that is affable and almost affectionate, as is customary

between enemies who are generous and worthy of mutual esteem, the Governor of Breda, who is bowing and

offering him the keys of the city in an attitude of noble humiliation.

Flags quartered with white and blue, their folds agitated by the wind, break in the happiest manner the straight

lines of the lances held upright by the Spaniards. The horse of the Marquis, represented almost foreshortened

from the rear and with its head turned, is a skilful invention to tone down military symmetry, so unfavourable

to painting.It would not be easy to convey in words the chivalric pride and the Spanish grandeur which distinguish the

heads of the officers forming the General’s staff. They express the calm joy of triumph, tranquil pride of race,

and familiarity with great events. These personages would have no need to bring proofs for their admittance

into the orders of Santiago and Calatrava. Their bearing would admit them, so unmistakably are they hidalgos.

Their long hair, their turned-up moustaches, their pointed beards, their steel gorgets, their corselets or their

buff doublets render them in advance ancestral portraits to hang up, with their arms blazoned on the corner of

the canvas, in the galleries of old castles. No one has known so well as Velasquez how to paint the gentleman

with such superb familiarity, and, so to speak, as equal to equal. He is by no means a poor, embarrassed artist

who only sees his models while they are posing and has never lived with them. He follows them in the privacy

of the royal apartments, on great hunting-parties, and in ceremonies of pomp. He knows their bearing, their

gestures, their attitudes, and their physiognomy; he himself is one of the King’s favourites (privados del

rey). Like themselves, and even more than they, he has les grandes et les petites entrées. The nobility

of Spain having Velasquez for a portrait-painter could not say, like the lion of the fable: “Ah! if the lions only

knew how to paint.”

Velasquez takes his place naturally between Titian and Van Dyck as a painter of portraits. His colour is

solidly and profoundly harmonious, without any false luxury and with no need of glitter. His magnificence is

that of ancient hereditary fortunes. It has tranquillity, equality, and intimacy. We find no violent reds, greens,

nor blues, no upstart glitter, no brilliant gew-gaws. All is restrained and subdued, but with a warm tone like

that of old gold, or with a grey tone like the dead sheen of family silver. Gaudy and loud things will do for

upstarts, but Don Diego Velasquez de Silva is too true a gentleman to make himself an object of remark in

that manner, and, let us say, too good a painter also. Although a realist, he brings to his art a lofty grandeur, a

disdain of useless detail, and an intentional sacrifice that plainly reveal the sovereign master. These sacrifices

were not always those that another painter would have made. Velasquez chose to put in evidence what, it

sometimes seems, should have been left in shadow. He extinguishes and he illuminates with apparent caprice,

but the effect always justifies him.The correctness of his eye was such that while he only pretended to be copying, he brought the soul to the

surface and painted the inner and the outer man at the same time. His portraits relate the secret Mémoires of

the Spanish court better than all the chroniclers. Let him represent them in gala dress, riding their genets, in

hunting-costume, an arquebuse in their hand, a greyhound at their feet, and we recognize in these wan figures

of kings, queens, and infantas, with pale faces, red lips, and massive chins the degeneracy of Charles V. and

the falling away of exhausted dynasties. Although a court-painter, he has not flattered his royal models.

However, despite the brainlessness of the type, the quality of these high personages would never be doubted.

It is not that he did not know how to paint genius; the portrait of the Count-Duke of Olivares, so noble, so

imperious, and so full of authority, unanswerably proves that, unable to lend any fire to these sad lords, he

gives them a cold majesty, a wearied dignity, a gesture and pose of etiquette, and then envelops all with his

magnificent colour; that was full payment for the protection of his crowned friend. M. Paul de Saint-Victor

has somewhere called Victor Hugo “The Spanish Grandee of poetry;” may we not be permitted to call

Velasquez “The Spanish Grandee of painting”? No qualification would suit him better.As we have said, Velasquez was Court Chamberlain, and it was he who was charged with the preparation of

the lodgings of the King in the trip that Philip IV. made to Irun to deliver the Infanta Doña Maria-Teresa to

the King of France. It was he who had decorated and ornamented the pavilion where the interview of the two

kings took place in the Île des Faisans. Velasquez was distinguished among the crowd of courtiers by his

personal dignity, the elegance, the richness, and the good taste of his costumes on which he arranged with art

the diamonds and jewels, — gifts of the sovereigns; but on his return to Madrid, he fell ill with fatigue and died

on the 7th of August, 1660. His widow, Doña Juana Pacheco, only survived him seven days and was interred

near him in the parish of San Juan. The funeral of Velasquez was splendid; great personages, knights of the

military orders, the King’s household, and the artists were present sad and pensive, as if they felt that with

Velasquez they were interring Spanish art.

Overview

Medium: Oil

Support: Canvas

Size: 307 cm x 367 cm

Art period: Baroque

Museo del Prado

Inventory number P01172

The following quote is from the catalog of the Velázquez exhibition in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1989 (1).

“In The Surrender of Breda, a work of absolute technical and conceptual maturity, Velázquez

achieves a prodigious balance between narrative-focusing with serenity and sober elegance

on the moment of the delivery of the keys, presenting conqueror and conquered on an equal

plane of chivalrous dignity-and execution, in which pulses a new perception of light and a

subtle counterposition of luminous colored planes. All memory of Caravaggio’s treatment

of lighted volumes has disappeared. Matter has become impalpable, seeming to soak in light

and at the same time radiate it, achieving a sensation of palpitation, of true life, created not

through tactile techniques – outlines are no longer sharply defined – but rather through

exclusively visual means. Velázquez’s technique had become fluid in the extreme, and occasionally

the pigments do not completely cover the canvas; areas of primer are visible, like the

paper of a watercolor.”

(1) Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez, Julián Gállego, Velázquez, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989, p. 38.

Pigments

Pigment Analysis

The following pigment analysis is based on the technical examination of Velázquez’s paintings in the Museo del Prado in Madrid (1).

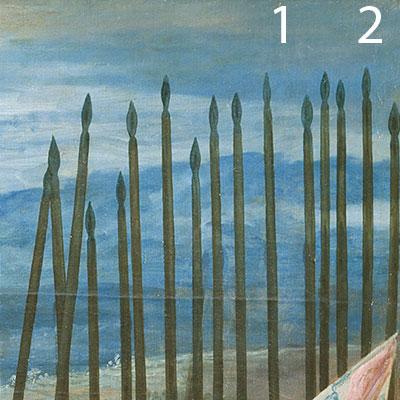

1 White ground, top edge: lead white with small amounts of calcite.

2 Blue sky: lead white, azurite with small amounts of charcoal black/bone black, red ochre and calcite.

3 White ground, top tacking edge: lead white with small amounts of calcite.

4 Green vegetation in lower edge near right corner: lead white, azurite, a yellow lake with small amounts of yellow ochre/red ochre, charcoal/bone black, calcite, and vermilion.

5 Blue-green sash of a boy dressed in a white coat: azurite and lead white.

6 Right pant leg of Dutch official with keys: bone black, yellow-brown ochre, lead white, calcite with a small amount of red lake.

7 Right pant leg of Spinola, near the top of the boot: lead white, red/yellow ochres, charcoal/bone black and calcite with small amounts of red lake, azurite, and smalt or glass.

8 Red sash of Spinola: red lake with small amounts of yellow ochre, bone black, and calcite.

9 Yellow-brown decoration at bottom of Spinola’s sash: lead white, yellow ochre with small amounts of calcite, charcoal/bone black, azurite, and red lake.

10 White collar of a man at far right: lead white with small amounts of calcite and possibly quartz.

11 Top of the left boot of the man in a turquoise dress: lead white, yellow/red ochres with small amounts of calcite, quartz, and charcoal/bone black.

12 Bootheel of a beige-coated man at left: yellow ochre, charcoal/bone black, lead white, gypsum with small amounts of red-brown ochre, red lake, and calcite.

13 Brown vegetation near the foot of beige-coated man: lead white, charcoal/bone black, brown ochre or umber, calcite, gypsum with small amounts of red lake and azurite.

14 Blue sky: several layers.

1 blue layer: lead white and azurite.

2 nearly white ground: lead white with some black and ochre.

15 The black mane of the horse: bone black with possibly an organic brown.

16 Green clump of vegetation below Spinola’s right foot: lead white, red/yellow ochres, calcite, green earth with small amounts of azurite and charcoal/bone black.

17 The brown-green ground at the right edge: several layers (from top to bottom)

1 pale orange-brown layer: clay-rich ochre and gypsum

2 blue-green layer: lead white, calcite, azurite, and yellow ochre

3 gray layer: indistinctly separated from layer no 2

4 gray-beige layer: lead white, calcite and ochre

5 grayish ground: lead white and charcoal black

18 Reddish-brown pant leg, the figure at left: several layers (from top to bottom)

1 discontinuous red-brown layer

2 discontinuous light red-brown layer

3 warm beige layer

4 beige layer, slightly redder than layer no 3

5 grayish ground

19 Brown-green ground, near the right edge: several layers (from top to bottom)

1 discontinuous orange-brown layer

2 discontinuous grayish-brown layer

3 discontinuous grayish-brown layer, slightly darker than no 2

4 grayish ground: lead white and charcoal black

20 Ground plane near the boot of soldier at left: several layers (from top to bottom)

1 orange-gray layer

2 gray ground: lead white and charcoal black

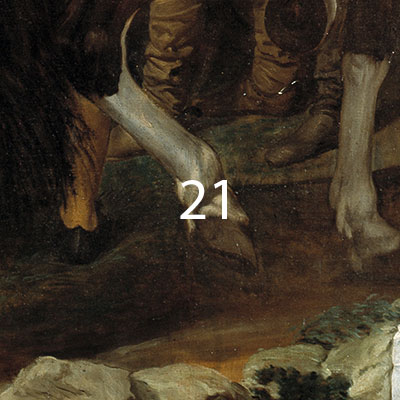

21 Horse’s hoof: several layers (from top to bottom)

1 gray layer overlain by a slightly lighter warm brownish-gray layer

2 gray ground: lead white and charcoal black

22 Blue uniform of a soldier at left: several layers (from top to bottom)

1 blue layer: lead white, azurite and glass or quartz, clay

2 beige-gray layer: lead white, ochre and glass or quartz

3 gray ground: lead white and charcoal black

References

(1) McKim-Smith, G., Andersen-Bergdoll, G., Newman, R. Examining Velazquez, Yale University Press, 1988, pp 118 – 120.

Pigments Used in This Painting

Resources

See the collection of online and offline resources such as books, articles, videos, and websites on Velázquez in the section ‘Resources on Painters‘

PowerPoint Presentations

Painting in Context: Velázquez, The Surrender of Breda

A richly illustrated presentation on the basic data, pigment analysis, and the pigments employed by Velázquez in this masterful depiction of the historical scene.

Number of slides: 18

Formats included in the download: PowerPoint Screen Presentation (ppsx) and pdf

Videos

Video: 'Velázquez, Surrender of Breda' by Museo del Prado (in Spanish)

Video: 'Velázquez, Surrender of Breda' by Artful Videos

Publications and Websites

Publications

(1) McKim-Smith, G., Andersen-Bergdoll, G., Newman, R. Examining Velazquez, Yale University Press, 1988.

(2) Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez, Julián Gállego, Velázquez, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 01.01.1989, pp. 110 – 115.

(3) Anthony Bailey, Velázquez and The Surrender of Breda: The Making of a Masterpiece, Henry Holt and Co, 2011.