Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne

1520-23Paintings sorted by Historical period | Painter | Subject matter | Pigments used

History of the Painting

Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne was one of the five masterpieces of Italian Renaissance paintings residing in the private gallery of Alfonso d’Este, the Duke of Ferrara. The Camerino d’Alabastro (Alabaster Room) in the ducal palace was – without a doubt – one of the most significant art collection projects of its time (1, 2, 3). With the help and under the influence of his sister, Isabella d’Este, he had commissioned paintings of mythological and bacchanalian subjects with Raphael, Dosso Dossi, Giovanni Bellini and Titian.

Copy after Titian, Alfonso I d’Este, the Duke of Ferrara, late 16th or early 17th century

The concept and planning for the Camerino d’Alabastro had been changed several times (1) and the final arrangement consisted of the following works: Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne, Worship of Venus and Bacchanal of the Andrians, Bellini’s (and Titian’s) Feast of the Gods and the Bacchanals of Men by Dosso Dossi.

Titian, The worship of Venus, 1518

Titian, Bacchanal of the Andrians, 1523-1524[/caption]

Giovanni Bellini and Titian, The Feast of Gods, 1514-29

The latter painting by Dossi is possibly lost, although it is sometimes being tentatively identified as the Bacchanal (Feast of Cybele) in the National Gallery in London.

It is worth noting that the myth of Bacchus and Ariadne was rare in Italian Renaissance painting in the early 16th century (1). Titian’s inspiration must have come from antique literary texts or possibly classical paintings or other visual artworks (2). Historical sources clearly show that Titian had been working on Bacchus and Ariadne for almost three years and the Duke was pressuring him to bring his work to fruition (1). The painting was finally completed in 1523.

Detailed provenance of the painting is described in reference (4).

References

(1) Cecil Gould, The Studio of Alfonso d’Este and Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne, National Gallery London, 1969.

(2) Raichel Le Goff, Re-creating Antiquity in the Renaissance: Alfonso d’Este’s Camerino d’Alabastro, presented as a postgraduate seminar at Oxford University 1995.

(3) Charles Hope, Camerini d’Alabastro’ of Alfonso d’Este-I, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 113, No. 824 (Nov. 1971), pp. 641-647+649-650.

(4) Provenance: Mapping Paintings | Bacchus and Ariadne

Related Paintings

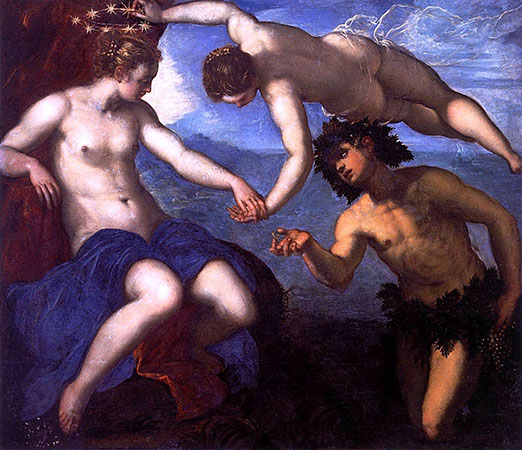

Jacopo Tintoretto, Bacchus and Ariadne, 1578

Oil on canvas, 146 x 157 cm

Palazzo Ducale, Venice, Italy

Guido Reni, Bacchus and Ariadne, 1621

Oil on canvas, 99 x 86 cm

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles

Allessandro Turchi, Bacchus and Ariadne, 1630-32

Oil on canvas, 114 x 148 cm

The Hermitage, St. Petersburg

Eustache Le Sueur, Bacchus and Ariadne, about 1640

Oil on canvas, 175.3 x 125.7

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Number 68.764

Jacob Jordaens, Bacchus and Ariadne, 1648

Oil on canvas, 121 x 127,2 cm

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Ferdinand Bol, Bacchus and Ariadne, 1664

Oil on canvas, 160,5 x 182,5 cm

The Hermitage, St Peterburg, Russia

Sebastiano Ricci, Bacchus and Ariadne, ca 1700-10

Oil on canvas, 75,9 x 63,2 cm

National Gallery London (NG851)

Antoine-Jean Gros, Bacchus and Ariadne, 1822

Oil on canvas, 90.8 x 105.7 cm

National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, (no. 18810)

Eugene Delacroix, Bacchus and Ariadne, 1856-63

Oil on canvas, 196 x 165 cm

São Paulo Museum of Art, São Paulo, Brazil

Overview

Medium: Oil

Support: Canvas

Size: 175.2 x 190.5 cm

Art period: High Renaissance

National Gallery London

Painting NG 35

Provenance: Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne, Mapping Paintings

‘Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne’ is one of the several paintings commissioned by the Duke of Ferrara for the Alabaster Room in the ducal palace.

Explore the story, pigment analysis, and history of this key masterwork of Italian Renaissance. Learn about other painters who depicted the story of Bacchus and Ariadne and watch videos about this painting.

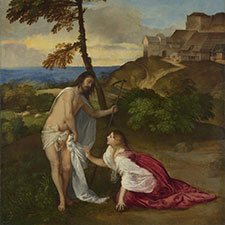

The Story of Bacchus and Ariadne

The Story

The story of Bacchus and Ariadne has its beginning, when princess Ariadne, daughter of the King Minos of Crete, helps the Athenian hero Theseus to slay the Minotaur residing in the center of the labyrinth. Ariadne gives Theseus a ball of thread whereupon Theseus ties one end of the thread to the door of the labyrinth and unfurls it as he progresses inside

He finds the beast Minotaur and kills him in an ensuing fight.

After escaping from the labyrinth using Ariadne’s thread, he sets sail to return to Athens taking Ariadne with him. The ship stops on the island of Naxos where Ariadne falls asleep and is abandoned by Theseus.

Theseus and Ariadne, House of L. Caecilius Jucundus, Pompeii, 1st century AD

In the painting below by the American painter John Vanderlyn Theseus boards his ship (far right in the middle) to abandon the sleeping Ariadne.

John Vanderlyn, Ariadne Sleeping on the island of Naxos (1809-14)

Now Ariadne disconsolately wanders the shores of Naxos, vainly looking for her lost lover Theseus.

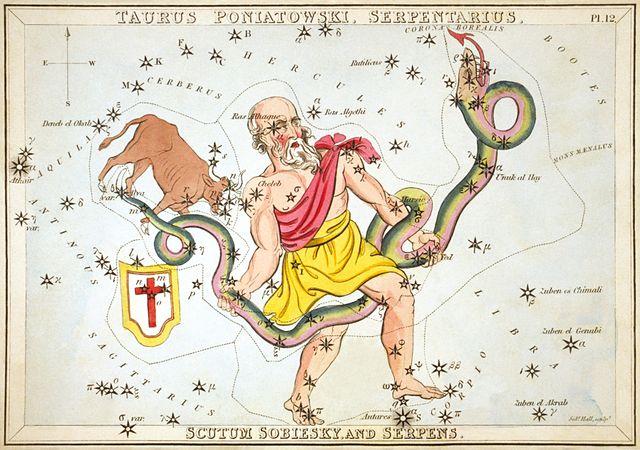

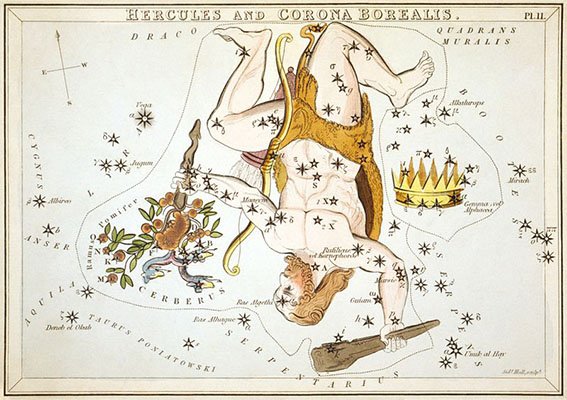

She is surprised by Bacchus and his inebriated and noisy entourage. Bacchus, the god of wine, falls in love with Ariadne and offers her marriage with the promise of a crown of stars as a wedding gift. In another version of the story, he offers her the Sky as a wedding gift where she later would become the constellation of the Northern Crown (Corona Borealis).

Sidney Hall, Urania’s Mirror, Hercules and Corona Borealis

Sidney Hall, Urania’s Mirror, Hercules and Corona Borealis

More than 380 images of Ariadne are included at the Warburg Institute Iconographic Database.

Classic Sources

An excellent discourse of Titian’s sources for this painting is given by Patrick Hunt (Stanford University) on the Philolog website (not anymore available on the web). One of the main questions being analyzed in this essay is whether Titian’s inspiration for Bacchus and Ariadne were texts such as Ovid and Catullus, or if he was at least partially inspired by surviving paintings or other visual art objects.

Influence of the poetry of Ovid on renaissance art

“With the rediscovery of classical antiquity in the Renaissance, the poetry of Ovid became a major influence on the imagination of poets and artists. His were among the first classical texts to benefit from the invention of printing in the late fifteenth century; they were widely and enthusiastically translated, and remained a fundamental influence on the diffusion and perception of Greek myths through subsequent centuries“ (1).

Origins of the Bacchus and Ariadne myth

“The Classical myth of Bacchus and Ariadne can be traced, as T. B. L. Webster (2) and others have shown, from Homer [e.g. Iliad XVIII.590 & Odyssey XI. 321] and Hesiod [Theogony 947 and Hymns to Dionysus VII & XXVI] to Hyginus [Fabulae 43] and on to Catullus [LXIV], Ovid and eventually Nonnus [Dionysiaca] in the 5th c.” (3)

Basic visual attributes of Bacchus (Dionysos) found in classical depictions

“As mentioned, the iconography of Bacchus or Dionysus is one of the most complex of all Greek and Roman deities, even as a relative newcomer “oriental” fertility god to Olympus.(24) There are at least ten recognizable attributes and many well-known vignettes in the corpus of Dionysian myth cycle [e.g. the “Birth of Dionysus”, “Dionysus and His Maenads”, Exekias’ “Dionysus and the Pirates”, “The Procession of Dionysus” and “Dionysus and Ariadne”] which would have been very familiar to most Greeks as well as specifically treated by such playwrights as Euripides [The Bacchae] and Aristophanes [The Frogs] since Dionysus was patron deity of dramatic tragedy and comedy. The very image of tragoedia was the death song or cry of the goat which invoked the god’s presence at a dramatic festival. As mentioned [infra n.5 of this paper], Philostratus [Imagines I.15] records this iconography as already developed in antiquity. Boardman and others (25) have shown through the range of black figure, red figure and white-ground vase painting that the manifold attributes of Dionysus / Bacchus include [1] the kantharos wine cup or rhyton drinking horn; [2] a grape or ivy leaf wreath in his hair; [3] an effeminate mode of dress [most emphatic when the mature wine god is bearded]; [4] the thyrsus, his ivy wand; [5] satyrs, whose half-goat features and untamable propensity to drunkenness and lust are the natural attestations of wildness and bestiality; [6] panthers as wild companions, steeds or drawing his chariot; [7] maenads or bacchantes, women who dance ecstatically to Phrygian flutes, drums or cymbals and tear apart forest animals, usually deer, or cavort with wild cats; [8] ivy leaves and tendrils; [9] Silenus, his drunken old companion who always seems about to fall off his donkey in a stupor; [10] bearded in black figure vase scenes; and, lastly [10] serpents.” (for sources in this quote see the original text by Hunt).

Classical texts by Ovid and Catullus

“Where would we most encounter Ovid in Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne? As mentioned, G.H. Thompson claimed Ovid is the most direct source in Ars Amatoria 1.527-64 (although a similar vignette is his Ars Amatoria 1.547-62), even more so than the Catullus Carmina LXIV [50-78, 116-43 & 254-64] or Ovid’s Fasti [3.459-516] and Metamorphoses [8.174-82]. Edgar Wind, of course, suggested the Fasti along with Catullus. (53) All of these passages have been much mentioned as literary sources for Titian’s painting. (54)

Ovid, Ars Armatoria

First, acknowledging the debt to Thompson, the Ars Amatoria 1. 527-64 passage can be summarized thusly. Ariadne [the Gnosian maid], after being abandoned and wandering on Naxos [Dia], has just awakened and is disconsolate about Theseus when the noisy frenzied retinue of Bacchus comes. She faints in fear at the sight, including drunken Silenus, and is then revived by the god who, after giving his reins to the tigers, promises her marriage with the crown of stars as nuptial gift. Bacchus then leaps down from his chariot to offset her fear at the tigers and bears her away, accompanied by the chanting of the holy revelers, `Euhoe!’ or `Hail, Hymeneus!’. Ovid concludes ” so do the bride and the god meet on the sacred couch” [line 564] :

Sic coeunt sacro nupta deusque toro.

Thus, in Ars Amatoria 1.527 & ff. we see Titian could have known this Ovidian version of the event, since these features are common to both: Ariadne’s loss over Theseus on Naxos, the Bacchic procession with drunken Silenus on his donkey and great cats pulling his chariot, the leaping of the god from chariot to earth, and the crown of stars. However, there is no serpent-writhed precedent in the foreground figure in Ovid’s account here.

Catulus, Carmen

Second, following the earlier attribution of the late 16th c. Lomazzo and mid-17th c. Ridolfi, Catullus’ Carmen LXIV with its Pelian embroidery depiction can also be summarized thusly. On the shore of Naxos, the just awakened and deserted Ariadne sees Theseus sailing away, and in her mindless desolation she has let all her garments slip down. In madness, she wanders up and down the island from rugged mountains to shore again. Elsewhere on the island, youthful Bacchus also wanders, seeking Ariadne with raging satyrs and Sileni crying ‘Evoe!, Evoe!‘, where some in the Bacchic processions wave thyrsi, toss mangled limbs of animals, gird themselves with writhing serpents, beat timbrels or clash cymbals with uplifted hands.

Thus, in Catullus’ poem we see Titian could have known this version of the event, since these features are common to both: Ariadne’s loss over Theseus on Naxos, the frenzied Bacchic procession with satyrs and sileni, specifically with satyrs waving thyrsi or animal limbs, the writhing serpent-girded figures, and timbrels and cymbals. However, Ariadne seems to be unclothed here and Silenus on his donkey doesn’t actually appear. There is no mention of the god’s chariot, Ariadne’s nuptial crown of stars [although it is mentioned in Carmen LXVI], or more important, no mention even of Ariadne actually meeting the god at all in Catullus LXIV. Noted by Lomazzo, Wind and Panofsky, the serpent-girded figure looms as perhaps the most important allusion to Catullus. Girded serpents, as mentioned previously, are not accidental to Bacchic processions [or thiasoi, initiate groups in Bober’s terms, op. cit.], as can be seen in the famous white-ground Brygos Cup [Munich 2647] of the maenad clutching a baby panther with a live snake girdle as her head-band (Fig. 8), as Eva Keuls states “More often Maenads are depicted with a snake coiled around one arm, in reference to the red-figure Kleophrades cup [Munich 2344], a detail referred to as “snake handling” (see image below), (55) which common feature we see on many other vases, e.g., the Attic Red-figure amphora by the Altamure painter around 470-50 BC from Capua [MS5466 – University Museum, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania] where snakes also appear on the figure’s head as a snake-girdled head-band.”

Ovid, Fasti

Third, acknowledging Edgar Wind’s attribution, Ovid’s Fasti 3.459-516 can be summarized thusly. Ariadne, doubly deserted by both Theseus and Bacchus on the `desert sands’ of Naxos, now rails at the faithless god who had previously rescued her while she paces the island shore. The god, returning from India to Naxos a second time, comes up behind her. He has heard her complaint and sweeps her into his arms, promising her heaven and immortality since they have already shared the bed, and changing her jeweled crown into nine stars. Thus in Fasti 3.459-516 we see Titian could have also known this other Ovidian version of the event, since these features are common to both: Ariadne’s loss over Theseus on Naxos, and the god returning to her with her crown transformed into stars. However, as Thompson argued, there is no riotous retinue of Bacchus and no chariot, and while many classical accounts, including Philostratus, allow for Ariadne to be found by Bacchus as asleep, not all require it, as Ars Amatoria 1 [and Catullus LXIV] make clear. T. B. L. Webster in Greece and Rome XIII.1, 1966, also evidences Ariadne as both asleep and awake through literature and vases, see infra, note 19 of this paper]. (for sources in this quote see the original text by Hunt)

Titian’s inspiration by classical objects of visual arts

Although these literary sources may have been uppermost in Titian’s imaginative reworking of the famous Ovidian story and Catullan poem, there could have been other visual stimuli alongside the Laocöon group so often mentioned, as amply demonstrated in the case made long ago by Otto Brendel, with many possible sources and models of classical art in Venice:

“It is not difficult to see that Titian was familiar with classical monuments from the beginning of his career, and that he grasped their style easily…it can be regarded as certain that Titian had a lasting interest in this ancient composition…The most conspicuous fact about his borrowings from ancient art is that the freedom with which Titian employed them increased with the years.”(66)

In this vein, another possible visual Classical model can be raised. In the Ian Jenkins and Kim Sloan catalog of the British Museum 1996 exhibition Vases and Volcanoes: Sir William Hamilton and His Collection, there is the so-called `Mantuan’ Gem [Figure 51, pp. 102-3] from 1st or 2nd c. CE Rome with its later historic period gold relief “pressing” [Figure 141, p. 238, where the photo is curiously reversed unless it is not a pressing but a copy]. The gemstone shows “a fema le figure, probably Ariadne, asleep on a chair. She is approached by Pan, a young satyr and – on the left – Bacchus with a torch and thyrsus, supported by Silenus.” Notable is the fact that it is a young Bacchus as in Titian’s painting. That this gem is very close to some of the earlier Ovidian and Philostratus accounts and equally close to some of the later Roman sarcophagi is readily apparent. Also important is that any pressing or secondary relief from the original would have Bacchus approaching from the right – just as in Titian’s painting. Naturally, not all is in agreement between the `Mantuan gem’ and Titian. Ariadne is asleep on the gem and awake in Titian, and yet Titian could have known the many Ovidian and Catullan quotations to Ariadne just waking from sleep and have staged his painting at this more interesting moment. There is also an inert Bacchus on the gem in contrast to Titian, which seems to better follow the literary format except that the Villa of the Mysteries [which Titian could not have yet seen at Pompeii] repeats a similarly inert Dionysus. Finally there is the Pan in the gem, although the so-called Laocoon and the child satyr in the foreground could both be somewhat derivable from the gemstone Pan if his attributes [animation – not ithyphallic condition, bestial face, horns and goat legs] were divided among them. (for sources in this quote see the original text by Hunt)

References

(1) L. Burn, Greek Myths: The Legendary Past. British Museum, 1990., p. 75.

(2) T. B. L. Webster, “The Myth of Ariadne from Homer to Catullus”, Greece and Rome XIII.1, 1966, 22-35; Pauly-Wissowa, Realencyclopadie der Classischen.

(3) H. D. Rouse, ed. and tr. Nonnos: Dionysiaca, vols. 1-3. Harvard, Loeb Classics, 1995. This 5th c. Egyptian recounting of the life of Dionysus relates his birth, Olympian entry, activities among mortals, amorous adventures [including Ariadne], and his conquest of India.

Ovid, Metamorphoses

Ovid, Metamorphoses

Translated by A. S. Kline © 2004 All Rights Reserved

Book VIII:152-182 The Minotaur, Theseus, and Ariadne

…

When Minos reached Cretan soil he paid his dues to Jove, with the sacrifice of a hundred bulls, and hung up his war trophies to adorn the palace. The scandal concerning his family grew, and the queen’s unnatural adultery was evident from the birth of a strange hybrid monster. Minos resolved to remove this shame, the Minotaur, from his house, and hide it away in a labyrinth of blind passageways. Daedalus, celebrated for his skill in architecture, laid out the design, and confused the clues to direction, and led the eye into a tortuous maze, by the windings of alternating paths. No differently from the way in which the watery Maeander deludes the sight, flowing backwards and forwards in its changeable course, through the meadows of Phrygia, facing the running waves advancing to meet it, now directing its uncertain waters towards its source, now towards the open sea: so Daedalus made the endless pathways of the maze, and was scarcely able to recover the entrance himself: the building was as deceptive as that.

In there, Minos walled up the twin form of bull and man, and twice nourished it on Athenian blood, but the third repetition of the nine-year tribute by lot, caused the monster’s downfall. When, through the help of the virgin princess, Ariadne, by rewinding the thread, Theseus, son of Aegeus, won his way back to the elusive threshold, that no one had previously regained, he immediately set sail for Dia, stealing the daughter of Minos away with him, then cruelly abandoned his companion on that shore. Deserted and weeping bitterly, as she was, Bacchus brought her help and comfort. So that she might shine among the eternal stars, he took the crown from her forehead, and set it in the sky. It soared through the rarified air, and as it soared its jewels changed to bright fires, and took their place, retaining the appearance of a crown, as the Corona Borealis, between the kneeling Hercules and the head of the serpent that Ophiuchus holds.

…

Ovid, Ars Armatoria

P. Ovidius Naso, Ars Amatoria, Book I

various, Ed.

…

Fair Ariadne wander’d on the shore

Forsaken now; and Theseus loves no more;

Loose was her gown, dishevel’d was her hair,

Her bosom naked, and her feet were bare;

Exclaiming, on the water’s brink she stood,

Her briny tears augment the briny flood;

She shriek’d and wept, and both became her face,

No posture could that heav’nly form disgrace.

She beat her breast: – “The traitor’s gone,” said she;

“What shall become of poor forsaken me?

What shall become-” She had not time for more,

The sounding cymbals rattled on the shore.

She swoons for fear, she falls upon the ground;

No vital heat was in her body found.

The Mimallonian dames about her stood,

And scudding satyrs ran before their god.

Silenus on his ass did next appear,

And held upon the mane (the god was clear).

The drunken sire pursues, the dames retire;

Sometimes the drunken dames pursue the drunken sire.

At last he topples over on the plain;

The satyrs laugh, and bid him rise again.

And now the god of wine came driving on,

High on his chariot by swift tigers drawn.

Her colour, voice, and sense forsook the fair;

Thrice did her trembling limbs for flight prepare,

And thrice affrighted did her flight forbear.

She shook like leaves of corn when tempests blow,

Or slender reeds that in the marshes grow.

To whom the god – “Compose thy fearful mind;

In me a truer husband thou shalt find.

With heav’n I will endow thee, and thy star

Shall with propitious light be seen afar,

And guide on seas the doubtful mariner.”

He said; and from his chariot leaping light,

Lest the grim tigers should the nymph affright,

His brawny arms around her waist he threw,

(For gods whate’er they please with ease can do,)

And swiftly bore her thence; th’ attending throng

Shout at the sight, and sing the nuptial song.

Now in full bowls her sorrow she may steep;

The bridegroom’s liquor lays the bride asleep

…

Catullus

Catullus, The Wedding of Peleus and Thetis

Translated by Thomas Bank, © All Rights Reserved

250-265

…

Thus fierce Theseus, entering the halls of his father’s house

now stained with death, received for himself the sort of grief he had brought with unmindful heart to the Minoan girl.

She, then, pitifully looking out at the receding boat, wounded, was spinning convoluted cares in her mind.

Then came swooping from somewhere Bacchus in his prime

with his cult of Satyrs, with his mountain-born Sileni,

seeking you, Ariadne, aflame with love for you.

Then too came raving, quick and everywhere, molten of mind,

with a “Bacchus!” the Bacchantes, with a “Bacchus!” convulsing

their heads. Some brandished ivy spears with leafy points.

Some tossed pieces of a ripped-apart bullock.

Some wreathed themselves with coiled snakes.

Some with deep baskets were celebrating mysterious rites,

rites that the uninitiate desire in vain to hear.

Others were striking drums, their palms raised highor were stirring shrill chimes with polished brass cymbals.

Horns were blowing hoarse blasts from many mouthsand primitive flutes squealed a bristling tune.

…

Composition of Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne

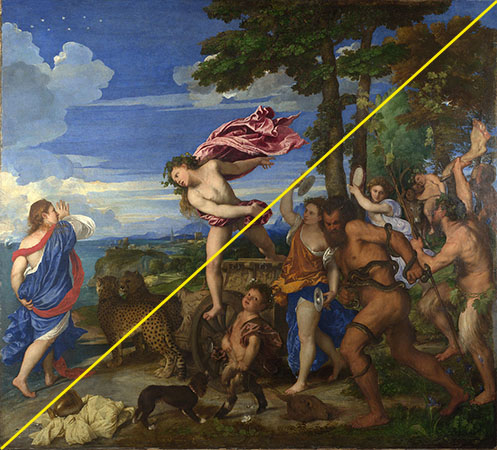

Composition

The painting is clearly divided into two parts by a diagonal line from the lower left to the upper right. On the left part, Ariadne is marching the shore with wide expanses of sea, sky, and open landscape in front of her. The right part is occupied by a noisy drunken procession of bacchants and satyrs marching in a darker and denser landscape representing the wild and animalistic side of life. Bacchus leaping from his carriage towards Ariadne in the center of the composition constitutes the pivotal element connecting both worlds.

Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne, 1523

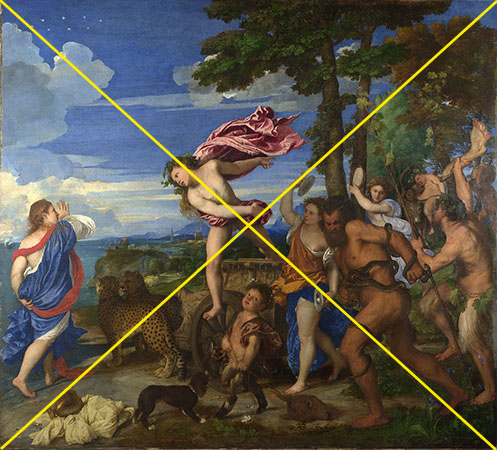

Adding the second diagonal from the upper left to the lower right reveals even further division of the composition.

Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne, 1523

The left quadrant belongs to the Minoan princess distraughtly wandering the shores, the upper quadrant is occupied by the leaping Bacchus. The right quadrant contains the rout of satyrs reveling in their wild rites. Now the lower quadrant contains the child satyr pulling a deer head behind him and a small pet dog attacking him. Patrick Hunt analyzes this peculiar feature as follows (1):

“One of Titian’s more inventive scenes in Bacchus and Ariadne is the confrontation between the satyr child [or faunus] and the dog. As a trophy of the wild orgiastic events in the woods where the Dionysiac rite of animal dismemberment usually take place, the satyr child drags a deer head on a string [probably belonging to the haunch of raw venison which one of the satyrs on the right is waving] whose blood and spoor the dog must have initially picked up. But now the dog – which the collar shows to be domesticated, perhaps as Ariadne’s pet – having just smelled the little satyr, appears to be confused: it has nosed forward, but its upper body is slightly backing up away from its feet. Its stance seems to be asking cautiously “What is this creature [the satyr] which smells both half-humanly familiar and half-wildly unfamiliar?” As he looks outward to us, the satyr child is enjoying this joke at the dog’s expense. Since there is no known classical precedent here, Titian has clearly inserted this little burlesque, perhaps for humorous effect, into the center foreground of the vignette.”

The figures in the painting deserve a closer look as well. First and foremost, Ariadne depicted between two episodes of her life − still mourning the loss of her lover and surprised by her future husband. She is the most refined and beautiful figure, even if Bacchus in the center of the composition is more prominent. Ariadne just barely takes notice of the leaping Bacchus, her heart still being preoccupied with Theseus and his deception. Titian depicts Ariadne in the precise decisive moment dividing her past and her future. Charles Lamb (2) puts it into following words:

“With the desert all ringing with the mad symbols of his followers, made lucid with the presence and new offers of a god, – as if unconcious of Bacchus, or but idly casting her eyes as upon some unconcerning pageant – her soul undistracted from Theseus – Ariadne is still pacing the solitary shore, in as much heart-silence, and in almost the same local solitude, with which she awoke at daybreak to catch the forlorn last glances of the sail that bore away the Athenian.

Here are two points miraculously co-uniting; fierce society, with the feeling of solitude still absolute; noon-day revelations, with the accidents of the dull grey dawn unquenched and lingering; the present Bacchus with the past Ariadne; two stories, with double Time; separate, and harmonizing.

Had the artist made the woman one shade less indifferent to the God; still more, had she expressed a rapture at his advent, where would have been the story of the mighty desolation of the heart previous? merged in the insipid accident of a flattering offer met with a welcome acceptance. The broken heart for Theseus was not lightly to be pieced up by God.”

The satyr with the snake could and indeed was sometimes falsely associated with the figure of Läocöon who was killed by snakes sent by Gods as punishment for his desecration of the temple of Apollo. But the satyr in this painting is not fighting the snakes in a mortal fight, he is, as described by Catullus, merely girding himself with writhing snakes (3):

Then too came raving, quick and everywhere, molten of mind,

with a “Bacchus!” the Bacchantes, with a “Bacchus!” convulsing

their heads. Some brandished ivy spears with leafy points.

Some tossed pieces of a ripped-apart bullock.

Some wreathed themselves with coiled snakes.

Some with deep baskets were celebrating mysterious rites,

rites that the uninitiate desire in vain to hear.

Others were striking drums, their palms raised high or were stirring shrill chimes with polished brass cymbals.

Horns were blowing hoarse blasts from many mouthsand primitive flutes squealed a bristling tune.

The drunken figure in the background on the far right on the back of the donkey is Silenus, the old companion, and tutor of Bacchus.

References

(1) P. Hunt, Philolog (Stanford University): Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne (1520-23) from Classical Art and Literature, 2006

(2) R.H. Shepherd, Ed., Lamb’s Complete Works, London, 1875. Included in Esther Singleton, Great Pictures as Seen and Described by Famous Writers, Dodd, Mead and Co., New York 1899

(3) Catullus, The Wedding of Peleus and Thetis, 250-265, translated by Thomas Bank, © All Rights Reserved

Composition Details

The composition is resplendent with interesting and sometimes peculiar details meriting a short description.

The star constellation (Northern Crown, Corona Borealis)

Above Ariadne, the star constellation of Northern Star (Corona Borealis) is visible in the upper left part of the painting.

The significance of this detail is described in the classical texts of Ovid in two versions. In his Metamorphoses (1) Bacchus throws the crown of Ariadne into the sky where it becomes the Northern crown:

“… Theseus, son of Aegeus, won his way back to the elusive threshold, that no one had previously regained, he immediately set sail for Dia, stealing the daughter of Minos away with him, then cruelly abandoned his companion on that shore. Deserted and weeping bitterly, as she was, Bacchus brought her help and comfort. So that she might shine among the eternal stars, he took the crown from her forehead, and set it in the sky. It soared through the rarified air, and as it soared its jewels changed to bright fires, and took their place, retaining the appearance of a crown, as the Corona Borealis, between the kneeling Hercules and the head of the serpent that Ophiuchus holds.”

In Ars Amatoria (2) Bacchus promises the entire sky to Ariadne where her own star will shine:

“Compose thy fearful mind;

In me a truer husband thou shalt find.

With heav’n I will endow thee, and thy star

Shall with propitious light be seen afar,

And guide on seas the doubtful mariner.”

Oddly enough, Titian painted the star constellation with eight stars while Ovid in his Fasti 3. 515 (3) clearly describes a crown of nine stars:

“… and I will see to it that

with thee there shall be a memorial of thy crown,

that crown which Vulcan gave to Venus, and she to

thee.” He did as he had said and changed the

nine jewels of her crown into fires. Now the golden

crown doth sparkle vidth nine stars.”

The reason for this discrepancy is not known.

The ship of Theseus

Just beside Ariadne’s left shoulder, the white sails of the ship carrying the treacherous Theseus away are seen in the distance.

Another inconsistency can be made out in this detail. According to the classical myth, Theseus sets sails for Crete on his dangerous mission to slay the Minotaur with black sails. He promised his father, the Athenian king Aegeus, to change his sails for white if he succeeded in defeating the Minotaur.

After having slain the Minotaur with the help of Ariadne he sails back to Athens with his ship still having black sails. But Theseus was upset and distracted after having abandoned Ariadne on the island of Naxos and had forgotten to put up white sails.

Aegeus was on the lookout for his son on a cliff and seeing the black sails he hurled himself into the sea. And to this day this part of the sea bears the name Aegean. Why Titian painted the sails in white is not clear either.

The animals drawing Bacchus’s chariot

The episode of Bacchus and Ariadne happened after Bacchus’s return from his successful military campaign in India. This explains the fact of Bacchus being frequently accompanied by leopards, lynxes, or tigers in classical paintings and texts.

Triumph of Bacchus, Mosaic from Sousse, Tunisia, 3rd century

In Ovid’s Ars Amatoria, Bacchus arrives at the scene where he encounters Ariadne in a chariot drawn by tigers (2):

“… And now the god of wine came driving on,

High on his chariot by swift tigers drawn.“

Now, the animals in Titian’s painting are no leopards or tigers but are definitely cheetahs. There are several interpretations given for this discrepancy. One reasonable explanation is given by Tresidder (4):

He mentions another literary work by a classic author who might have served Titian as inspiration for his painting: “Imagines” by Philostratus the Elder. In this text, Philostratus describes Bacchus’ devotion to animals which leap lightly like a bacchante. The name of the animal in the original text is ‘pardalis’, which should be translated as ‘leopard’.

Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne, 1523, detail

Alfonso d’Este was known to have borrowed a copy of “Imagines” by Philostratus the Elder from his sister Isabella. The important point here is that Isabella’s copy of the “Imagines” was a translation into Italian by a greek scholar Demetrius Moscus. As Tressider states:

This translation was thought to have been lost, but its recent discovery

in the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris enables us to

understand why cheetahs appear in Titian’s painting. As

stated above, the standard modern English translation of

Philostratus’s pardalis ‘leopard’ or ‘leopardess’. Moscus,

however, sometimes translates the Greek term into Italian as

leopardo and sometimes as pardo. Nevertheless, he was not

being any more inconsistent than his contemporaries because

pardo, panthera and leopardo appear to have been used in the

fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries to describe any of the

large cats. The words ghepardoa nd gattopardow, hich are used in

modern Italian for cheetahs, came into common usage somewhat

later, as did the English term. Nevertheless, cheetahs,

although rare, were in fact better known in Italy in Titian’s

time than any other variety of exotic, spotted carnivorous

feline. There is ample evidence to prove that they were used by

the nobility (including that of Ferrara), as hunting animals.

References

(1) Ovid, Metamorphoses, translated by A. S. Kline © 2004 All Rights Reserved, Book VIII:bv152-182 The Minotaur, Theseus, and Ariadne

(2) P. Ovidius Naso, Ars Amatoria, Book I, Perseus Catalog

(3) P. Ovidius Naso, Fasti, translated by J.G. Frazer, Loeb Classical Library, William Heinemann London, 1931

(4) Tresidder, Warren, The Cheetahs in Titian’s ‘Bacchus and Ariadne‘, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 123, No. 941 (Aug. 1981), pp. 481-483+485

Text by Ch. Lamb

Charles Lamb, Bacchus and Ariadne by Titian

R.H. Shepherd, Ed., Lamb’s Complete Works, London, 1875

Included in Esther Singleton, Great Pictures as Seen and Described by Famous Writers, Dodd, Mead and Co., New York 1899.

“Hogarth excepted, can we produce any one painter within the last fifty years, or since the humour of exhibiting began, that has treated a story imaginatively? By this we mean, upon whom has subject so acted that it has seemed to direct him – not to be arranged by him? Any upon whom its leading or collateral points have impressed themselves so tyrannically, that he dared not to treat it otherwise, lest he should falsify a revelation? Any that has imparted to his compositions, not merely so much truth as is enough to convey a story with clearness, but that individualizing property, which should keep the subject so treated distinct in feature from every other subject, however similar, and to common apprehensions almost identical; so as that we might say this and this part could have found an appropriate place in no other picture in the world but this?

Is there anything in modern art – we will not demand that it should be equal – but in any way analogous to what Titian effected, in that wonderful bringing together of two times in the Ariadne, in the National Gallery? Precipitous, with his reeling Satyr rout about him, repeopling and re-illumining suddenly the waste places, drunk with a new fury beyond the grape, Bacchus, born in fire, fire-like flims himself at the Cretan.

This is the time present. With this telling of the story an artist, and no ordinary one, might remain richly proud. Guido in his harmonious version of it, saw no farther. But from the depths of the imaginative spirit, Titian has recalled past time, and laid it contributory with the present to one simultaneous effect.”

Guido Reni-Bacchus-and-Ariadne-1621

[Note: Image not included in the original text. See also ‘Related paintings‘ on this webpage.]

With the desert all ringing with the mad symbols of his followers made lucid with the presence and new offers of a god, – as if unconscious of Bacchus, or but idly casting her eyes as upon some unconcerning pageant – her soul undistracted from Theseus – Ariadne is still pacing the solitary shore, in as much heart-silence, and in almost the same local solitude, with which she awoke at daybreak to catch the forlorn last glances of the sail that bore away the Athenian.

Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne, detail

[Note: Images not included in the original text. See also ‘The Story‘ on this webpage.]

Here are two points miraculously co-uniting; fierce society, with the feeling of solitude still absolute; noon-day revelations, with the accidents of the dull grey dawn unquenched and lingering; the present Bacchus with the past Ariadne; two stories, with double Time; separate, and harmonizing.

Had the artist made the woman one shade less indifferent to the God; still more, had she expressed a rapture at his advent, where would have been the story of the mighty desolation of the heart previous? merged in the insipid accident of a flattering offer met with a welcome acceptance. The broken heart for Theseus was not lightly to be pieced up by God.

Text by E.-T. Cook

Edward T. Cook, Bacchus and Ariadne by Titian

E.T. Cook, Popular Handbook to the National Gallery, London and New York 1888

Included in Esther Singleton, Great Pictures as Seen and Described by Famous Writers, Dodd, Mead and Co., New York 1899.

But though as yet half unconscious, Ariadne is already under her fated star; for above is the constellation of Ariadne’s crown – the crown with which Bacchus presented his bride. And observe in connections with the astronomical side of the allegory the figure of Bacchus’s train with the serpent round him: this is the serpent-bearer (Milton’s “Ophiuchus huge”) translated to the skies with Bacchus and Ariadne.

Ophiuchus holding the serpent, Serpens, as depicted in Urania’s Mirror

[Note: Image not included in the original text]

Notice too another piece of poetry: the marriage of Bacchus and Ariadne took place in the spring, Ariadne herself being the personification of its return, and Bacchus of its gladness; hence the flowers in the foreground which deck his path.

The picture is full of painter’s art as of the poet’s. Note first the exquisite painting of the wine leaves, and of these flowers in the foreground, as an instance of the “constant habit of the great masters to render every detail of their foreground with the most laborius botanical fidelity.

“The foreground is occupied with the common blue iris, the aquilegia, and the wild rose (more correctly Capparis Spinosa); every stamen of which latter is given, while the blossoms and leaves of the columbine (a difficult flower to draw) have been studied with the most exquisite accuracy.”

But this detail is sought not for its own sake, but only so far as is necessary to mark the typical qualities of beauty in the object. Thus “while every stamen of the rose is given because this was necessary to mark the flower, and while the curves and large characters of the leaves are rendered with exquisite fidelity, there is no vestige of particular texture, of moss, bloom, moisture, or any other accident, no dewdrops, nor flies, nor trickeries of any kind: nothing beyond the simple forms and hues of the flowers, even those hues themselves being simplified and broadly rendered. The varieties of aquilegia have in reality a greyish and uncertain tone of colour, and never attain the purity of blue with which Titian has gifted his flower. But the master does not aim at the particular colour of individual blossoms; he seizes the type of all, and gives it with the utmost purity and simplicity of which colour is capable.”

A second point to be noticed is the way in which one kind of truth has often to be sacrificed in order to gain another. Thus here Titian sacrifices truth of aërial effect to richness of tone – tone in the sense, that is, of that quality of colour whim makes us feel that the whole picture is in one climate, under one kind of light, and in one kind of atmosphere.

Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne, detail

[Note: Image not included in the original text]

“It is difficult to imagine anything more magnificently impossible than the blue of the distant landscape; impossible, not from its vividness, but because it is not faint and aërial enough to account for its purity of colour; it is too dark and blue at the same time; and there is indeed s total want of atmosphere in it, that, but for the difference of form, it would be impossible to tell the mountains intended to be ten miles off, from the robe of Ariadne close to the spectator. Yet make this blue faint, aërial, and distant; make it in the slightest degree to resemble the tint of nature’s colour; and all the tone of the picture, all the intensity and splendor will vanish on the instant.” (1)

We may notice lastly what Sir Joshua Reynolds (Discourse VIII.) points out, that the harmony of the picture – that wonderful bringing together of two times of which Lamb speaks above, is assisted by the distribution of colours.

“To Ariadne is given (say the critics) a red scarf to relieve the figure from the sea, which is behind her. It is not for that reason alone, but for another of much greater consequence; for the sake of the general harmony and effect of the picture. The figure of Ariadne is separated from the great group, and is dressed in blue, which added to the colour of the sea, makes the quantity of cold colour which Titian thought necessary for the support and brilliance of the great group; which group is composed, with very little exception, entirely of mellow colours.

But as the picture, in this case, would be divided into two distinct parts, one half cold, and the other warm; it was necessary to carry some of the mellow colours of the great group into the cold part of the picture, and a part of the cold into the great group; accordingly, Titian gave Ariadne a red scarf, and to one of the Bacchante a little blue drapery.”

Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne, detail

[Note: Images not included in the original text. See also ‘Pigments’ on this website]

It is interesting to know that this great picture took Titian three years, off and on, to finish. It was a commission from the Duke of Ferrara, who supplied canvas and frame for it, and repeatedly wrote to press for its delivery; it reached him in 1523.

References in the original text

(1) John Ruskin, Modern Painters, Vols I., XXVII., XXX. (Preface to Second Edition). pt. i sec ii. ch 1. § 5, pt ii. sec. ii. ch. 1. § 15; Vol III. pt. iv. ch. ix. § 18; Vol V. pt. ix. ch. iii. § 31; Arrows of the Chace, I. 58

Pigments and Handling of Colour

Titian's Handling of Colour

Titian was the recognized master of colors and Bacchus and Ariadne is a shining example of his capabilities. The left part of the composition is painted in cool colors dominated by the blue of the sky and the distant landscape and by the blue robe of Ariadne. Deep green and warm earthen brown tones on the right side emphasize the wild and naturalistic part of the composition.

But Titian did not stop at this simple color distribution. As Sir Joshua Reynolds remarks in his Discourse VIII (1), he refines the color harmony by using color contrasts in both parts of the picture:

“To Ariadne is given (say the critics) a red scarf to relieve the figure from the sea, which is behind her. It is not for that reason alone, but for another of much greater consequence; for the sake of the general harmony and effect of the picture. The figure of Ariadne is separated from the great group, and is dressed in blue, which added to the colour of the sea, makes the quantity of cold colour which Titian thought necessary for the support and brilliancy of the great group; which group is composed, with very little exception, entirely of mellow colours.

But as the picture in this case would be divided into two distinct parts, one half cold, and the other warm; it was necessary to carry some of the mellow colours of the great group into the cold part of the picture, and a part of the cold into the great group; accordingly, Titian gave Ariadne a red scarf, and to one of the Bacchante a little blue drapery.”

References

(1) Joshua Reynolds, The Discourses of Sir Joshua Reynolds (Google eBook) (1842), p. 157, quoted in Edward T. Cook, Bacchus and Ariadne by Titian. The copy of the original text can be found on this website.

Pigment Analysis

The painting was restored in 1967-69 by conservators of the National Gallery in London. A shorter description for educational purposes has been put together by the Royal Society of Chemistry in collaboration with National Gallery in London: Royal Society of Chemistry, The Chemistry of Art: Bacchus and Ariadne (Tutorial)

The pigment analysis is based on the work of the scientists at the National Gallery London published as Lucas, A., Plesters, J. ‘Titian’s “Bacchus and Ariadne“‘. National Gallery Technical Bulletin Vol 2, pp 25–47.

The authors of the above publication describe the availability of pigments in 16th-century Venice as follows:

“Venetian sixteenth-century painting has always been famous for its colour. Venice was in an enviable position with regard to supplies of pigments, being not only the port through which exotic materials like lapis lazuli entered Europe from the East, but also a centre of the textile and dyeing industry and famous for its lake pigments which were a byproduct of the latter. Titian, as a successful painter with wealthy clients, would have had first pick of all the materials from the point of view of both of variety and quality.”

1 Ariadne’s cloak, the sky, the distant landscape, and the blue drapery of the Bacchante with the cymbals are painted in high-quality natural ultramarine mixed with lead white.

2 The sea and the greenish parts of the distant landscape are painted in azurite.

3 Green foliage left of Bacchus: above the ground is a double layer of yellow ochre, then an underpainting of green earth and lead white, followed by a layer of azurite and lead white. The top layer consists of malachite and lead white glazed over by a browned copper resinate glaze.

4 Bright green foliage: verdigris and copper resinate (verdigris solved in a mixture of a resin and oil). The brown parts of the foliage are an example of the discolouring of copper resinate with age.

5 The brown colour of this tree is not due to discoloured copper resinate but was painted in yellow and brown ochre.

6 Titian employed finely ground vermilion for Ariadne’s scarlet red sash.

7 Bacchus’s crimson drapery: red lake pigment which was not further identified. It could be either madder or carmine lake.

8 The yellow drapery beneath the urn is painted in lead-tin yellow type I.

9 and 10 The orange drapery of the Bacchante with the cymbals contains realgar as the main pigment with the highlights painted in orpiment.

11 The pale mauve drapery of the Bacchante with the tambourine is painted in a mixture of natural ultramarine, lead white and a little red lake.

Pigments Used in This Painting

Resources

See the collection of online and offline resources such as books, articles, videos, and websites on Titian in the section ‘Resources on Painters‘

PowerPoint Presentations

Videos

Video: 'Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne' by National Gallery London

Video: 'Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne' by National Gallery London

Video: 'Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne, Painting the Story' by National Gallery London

Video: 'Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne, Painting the Myth' by National Gallery London

Video: 'Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne' by Smarthistory

Publications and Websites

Publications

(1) P. Hunt, Philolog (Stanford University): Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne (1520-23) from Classical Art and Literature, 2006

(2) R.H. Shepherd, Ed., Lamb’s Complete Works, London, 1875. Included in Esther Singleton, Great Pictures as Seen and Described by Famous Writers, Dodd, Mead and Co., New York 1899

(3) Catullus, The Wedding of Peleus and Thetis, 250-265, translated by Thomas Bank, © All Rights Reserved

(4) Tresidder, Warren, The Cheetahs in Titian’s ‘Bacchus and Ariadne‘, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 123, No. 941 (Aug. 1981), pp. 481-483+485

(5) Cecil Gould, The Studio of Alfonso d’Este and Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne, National Gallery London, 1969.

(6) Raichel Le Goff, Re-creating Antiquity in the Renaissance: Alfonso d’Este’s Camerino d’Alabastro, presented as a postgraduate seminar at Oxford University 1995.

(7) Charles Hope, Camerini d’Alabastro’ of Alfonso d’Este-I, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 113, No. 824 (Nov. 1971), pp. 641-647+649-650.

(8) Lucas, A., Plesters, J. ‘Titian’s “Bacchus and Ariadne“‘. National Gallery Technical Bulletin Vol 2, pp 25–47.

(9) Royal Society of Chemistry, The Chemistry of Art: Bacchus and Ariadne (Tutorial)

Websites

Mapping Paintings | Bacchus and Ariadne