Titian, Diana and Actaeon

1556-59Paintings sorted by Historical period | Painter | Subject matter | Pigments used

Related Paintings: Titian's Poesie Paintings

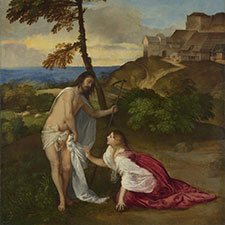

Titian painted a series of paintings with mythological subjects for King Philip II of Spain. Inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses, they are among Titian’s most admired works (1 and 2).

Quote from the website of DeYoung Museum San Francisco

“Titian and the Poesie

Among Titian’s most breathtaking works is a series of mythological subjects known as the poesie, which celebrate the loves of

ancient gods, goddesses, and mortals. In paintings of deep, sonorous color and broken, expressive brushwork, Titian created a visual

equivalent to lyric and emotive forms of poetry. The erotic beauty of the nude female form, often encompassed in the thick atmosphere of a pastoral landscape, is the focus of these compositions. Titian’s classical literary sources, especially the Metamorphoses, completed by the Roman author Ovid around AD 8, provide a veneer of respectability for these remarkable paintings. Ultimately, however, Titian’s poesie explore a world of physical sensuality that is made palpable through his brilliant technique. Designed for the pleasure of the male viewer, paintings such as Danaë were sought after by collectors and often replicated by the artist to satisfy the requests of noble patrons.”

The Poesie paintings

Danaë with a Nurse or Danaë Receiving the Golden Rain, 1553-54, Museo del Prado, Madrid

Danaë, ca 1554, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Russia

Danaë with Eros, 1544, Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte, Naples. Italy

Titian, Danaë with Nursemaid or Danaë Receiving the Golden Rain, 1560s. Museo del Prado

Venus and Adonis, 1554, The J. Paul Getty Museum

Venus and Adonis, 1554, Museo del Prado

Venus and Adonis, ca 1560, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Rome

Venus and Adonis, ca 1560, National Gallery of Art Washington

Venus and Adonis, ca 1554, National Gallery London

Titian, Venus and Adonis, 1555-60, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Diana and Actaeon, 1556-59, National Gallery London and National Galleries of Scotland

Titian, Diana and Actaeon, 1556-59, National Gallery London

Diana and Callisto, 1556-59, National Gallery London

Titian, Diana and Callisto, 1556-59, National Gallery London

Rape of Europa, 1559-62, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Titian, Rape of Europa, 1559-62, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston

Death of Actaeon, 1562, National Gallery London

Titian, Death of Actaeon, 1562, National Gallery London

Titian, Perseus and Andromeda, 1554-56, Wallace Collection London

Titian, Tarquin and Lucretia, 1568-71, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

Titian, Tarquin and Lucretia, 1568-71, Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

References

(1) Tanner, M, Sublime Truth and the Senses: Titian’s Poesi (Studies in Medieval and Early Renaissance Art History), Brepols N.V., 2019

(2) National Gallery London, Titian’s ‘poesie’ paintings. [Accessed 30 Jul. 2017].

The Story of Diana and Actaeon

Ovid, Metamorphoses Book III (A. S. Kline’s Version)

Bk III: 138-164 Actaeon returns from the hunt

Actaeon, one of your grandsons, was your first reason for grief, in all your happiness, Cadmus. Strange horns appeared on his forehead, and his hunting dogs sated themselves on the blood of their master. But if you look carefully, you will find that it was the fault of chance and not wickedness: what wickedness is there in error? It happened on a mountain, stained with the blood of many creatures, and midday had contracted every shadow and the sun was equidistant from either end of his journey. Then Actaeon, the young Boeotian, with a quiet expression, spoke to his companions in the hunt as they wandered through the solitary wilds ‘Friends, our spears and nets are drenched with the blood of our victims, and the day has been fortunate enough. When Aurora in her golden chariot brings another day we will resume our purpose. Now Phoebus is also between the limits of his task, and is splitting open the earth with his heat. Finish your present task and carry home the netted meshes’ The men obeyed his order and left off their labour.

There was a valley there called Gargaphie, dense with pine trees and sharp cypresses, sacred to Diana of the high-girded tunic, where, in the depths, there is a wooded cave, not fashioned by art. But ingenious nature had imitated art. She had made a natural arch out of native pumice and porous tufa. On the right, a spring of bright clear water murmured into a widening pool, enclosed by grassy banks. Here the woodland goddess, weary from the chase, would bathe her virgin limbs in the crystal liquid.

Bk III: 165-205 Actaeon sees Diana naked and is turned into a stag.

Having reached the place, she gives her spear, quiver and unstrung bow to one of the nymphs, her weapon-bearer. Another takes her robe over her arm, while two unfasten the sandals on her feet. Then, more skilful than the rest, Theban Crocale gathers the hair strewn around her neck into a knot, while her own is still loose. Nephele, Hyale, Rhanis, Psecas and Phiale draw water, and pour it over their mistress out of the deep jars.

While Titania is bathing there, in her accustomed place, Cadmus’s grandson, free of his share of the labour, strays with aimless steps through the strange wood, and enters the sacred grove. So the fates would have it. As soon as he reaches the cave mouth dampened by the fountain, the naked nymphs, seeing a man’s face, beat at their breasts and filling the whole wood with their sudden outcry, crowd round Diana to hide her with their bodies. But the goddess stood head and shoulders above all the others. Diana’s face, seen there, while she herself was naked, was the colour of clouds stained by the opposing shafts of sun, or Aurora’s brightness.

However, though her band of nymphs gathered in confusion around her, she stood turning to one side, and looking back, and wishing she had her arrows to hand. She caught up a handful of the water that she did have, and threw it in the man’s face. And as she sprinkled his hair with the vengeful drops she added these words, harbingers of his coming ruin, ‘Now you may tell, if you can tell that is, of having seen me naked!’ Without more threats, she gave the horns of a mature stag to the head she had sprinkled, lengthening his neck, making his ear-tips pointed, changing feet for hands, long legs for arms, and covering his body with a dappled hide. And then she added fear. Autonoë’s brave son flies off, marveling at such swift speed, within himself. But when he sees his head and horns reflected for certain in the water, he tries to say ‘Oh, look at me! but no voice follows. He groans: that is his voice, and tears run down his altered face. Only his mind remains unchanged. What can he do? Shall he return to his home and the royal palace, or lie hidden in the woods? Shame prevents the one, and fear the other.

Bk III: 206-231 Actaeon is pursued by his hounds

While he hesitates his dogs catch sight of him. First ‘Black-foot’, Melampus, and keen-scented Ichnobates, ‘Tracker’, signal him with baying, Ichnobates out of Crete, Melampus, Sparta. Then others rush at him swift as the wind, ‘Greedy’, Pamphagus, Dorceus, ‘Gazelle’, Oribasos, ‘Mountaineer’, all out of Arcady: powerful ‘Deerslayer’, Nebrophonos, savage Theron, ‘Whirlwind’, and Laelape, ‘Hunter’.

Then swift-footed Pterelas, ‘Wings’, and trail-scenting Agre, ‘Chaser’, fierce Hylaeus, ‘Woody’, lately gored by a boar, the wolf-born Nape, ‘Valley’, Poemenis, the trusty ‘Shepherd’, and Harpyia, ‘Snatcher’, with her two pups. There is thin-flanked Sicyonian Ladon, ‘Catcher’, Dromas, ‘Runner’, ‘Grinder’, Canache, Sticte ‘Spot’, Tigris ‘Tigress’, Alce, ‘Strong’, and white-haired Leucon, ‘Whitey’, and black-haired Asbolus, ‘Soot’.

Lacon, ‘Spartan’, follows them, a dog well known for his strength, and strong-running Aëllo, ‘Storm’. Then Thoos, ‘Swift’, and speedy Lycisce, ‘Wolf’, with her brother Cyprius ‘Cyprian’. Next ‘Grasper’, Harpalos, with a distinguishing mark of white, in the centre of his black forehead, ‘Black’, Melaneus, and Lachne, ‘Shaggy’, with hairy pelt, Labros, ‘Fury’, and Argiodus, ‘White-tooth’, born of a Cretan sire and Spartan dam, keen-voiced Hylactor, ‘Barker’, and others there is no need to name. The pack of them, greedy for the prey follow over cliffs and crags, and inaccessible rocks, where the way is hard or there is no way at all. He runs, over the places where he has often chased, flying, alas, from his own hounds. He longs to shout ‘I am Actaeon! Know your own master!’ but words fail him, the air echoes to the baying.

Bk III: 232-252 Actaeon is killed by the dogs

First ‘Black-hair’, Melanchaetes, wounds his back, then ‘Killer’, Theridamas, and Oresitrophos, the ‘Climber’, clings to his shoulder. They had set out late but outflanked the route by a shortcut over the mountains. While they hold their master the whole pack gathers and they sink their teeth in his body till there is no place left to wound him. He groans and makes a noise, not human, but still not one a deer could make, and fills familiar heights with mournful cries. And on his knees, like a suppliant begging, he turns his wordless head from side to side, as if he were stretching arms out towards them.

Now his friends, unknowingly, urge the ravening crowd of dogs on with their usual cries, looking out for Actaeon, and shouting, in emulation, for absent Actaeon (he turning his head at the sound of his name) complaining he is not there, and through his slowness is missing the spectacle offered by their prey. He might wish to be absent it’s true, but he is here: he might wish to see and not feel the fierce doings of his own hounds. They surround him on every side, sinking their jaws into his flesh, tearing their master to pieces in the deceptive shape of the deer. They say Diana the Quiver-bearer’s anger was not appeased, until his life had ended in innumerable wounds.

Titian, Death of Actaeon, 1559-75

Titian, Death of Actaeon, 1559-75

Overview

Medium: Oil

Support: Canvas

Size: 184.5 x 202.2 cm

Art period: High Renaissance

National Gallery London and National Galleries of Scotland

Inventory number: NG6611

One of the “poesie” paintings painted for King Philip II of Spain featuring goddess Diana being surprised by young Actaeon while bathing in the forest with her group of nymphs and servants. This is one of the series of ‘poesie’ paintings with mythological subjects painted for King Philip II of Spain. Inspired by Ovid’s Metamorphoses, they are among Titian’s most admired works.

Titian employed an extensively wide palette of nearly all pigments known in the Renaissance such as vermilion, red lead, natural ultramarine, smalt, verdigris, malachite, ochres, and lead-tin yellow.

Diana and Actaeon, Diana and Callisto, and The Death of Actaeon were hung together as part of the spectacular multi-arts project Metamorphosis: Titian 2012 staged jointly by the National Gallery London and the Royal Opera House.

Pigments

Pigment Analysis

The following pigment analysis is based on the work of scientists at the National Gallery London (1). Titian made several significant changes to the composition as has been shown by x-ray radiography and infrared reflectography and confirmed by the pigment analysis.

1 Actaeon’s muscle: three upper layers of flesh paint consisting of lead white, yellow ochre, brown ochre, vermilion, and a little umber. The lowest layer consists of lead white, red lake, and some discoloured smalt.

2 Blue sky: two layers of natural ultramarine mixed with lead white cover the original position of Actaeon’s head. The layers belonging to the flesh paint of Actaeon’s head contain lead white, red lake, vermilion, and a little black.

3 Crimson drapery above Actaeon: several layers consisting of red lake, vermilion, red lead, and white in varying proportions.

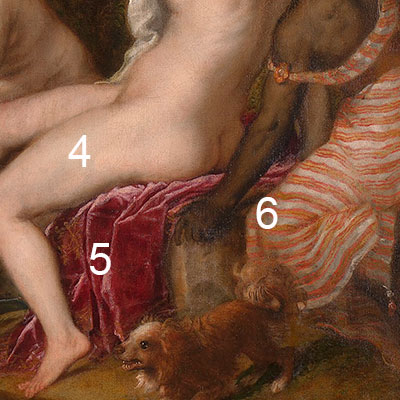

4 Diana’s flesh: at least four layers based on lead white, vermilion, red lake, yellow ochre, some black, and in one layer natural ultramarine.

5 Cool purple-red cloth on which Diana is seated: probably layers of red glaze interspersed with mixtures of red lake and lead white.

6 Stripped dress of the black maidservant: the orange stripes are painted with a mixture of lead white, vermilion, red lake, and a little lead-tin yellow. The brighter beige stripes contain yellow ochre.

7 Orange lining of Actaeon’s shoes: vermilion painted over a darker red layer containing some red lake as well.

8 Lilac drapery: the top layers contain lead white, red lake, and natural ultramarine. The uppermost layer forming the shadow consists of ultramarine and only a little lead white and red lake. Under these layers, there are several beige layers consisting of lead white, vermilion, red lake, ochres, umber, and some black. The lower layers are presumably the flesh paint of the nymph’s thigh originally not covered with the cloth.

9 Brown foreground: translucent browns interspersed with more opaque layers containing lead-tin yellow and yellow ochre.

10 Decorative orange lines on the arches: vermilion, perhaps with a little red lead applied over strokes of yellow earth.

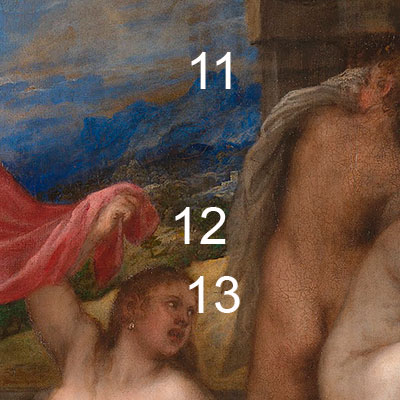

11 Blue mountains: uppermost layer of high-quality natural ultramarine mixed with very little lead white. Beneath this layer is a thick layer of discoloured smalt mixed with lead white. The lowest layer of yellow ochre and red ochre, umber, red lead, black, and lead white belongs to the original stone pillars later overpainted by Titian.

12 Landscape in the middle distance: the uppermost layer consists of malachite mixed with a little lead-tin yellow and ultramarine. Below this is a translucent layer containing darkened verdigris, some discoloured smalt, and a little lead white, lead-tin yellow and ultramarine.

13 Bright sunlit field: lead-tin yellow with some red lead and yellow ochre.

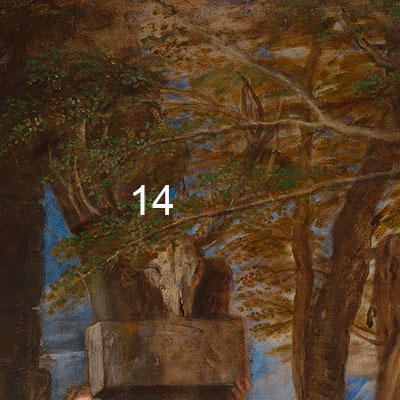

14 Foliage of the trees behind Diana: some of the leaves might have been brown from the beginning, others are dark due to discoloured verdigris. The green foliage is painted using verdigris and lead-tin yellow. The bright green leaves in front of the stag skull are painted in malachite.

References

(1) Jill Dunkerton and Marika Spring. With contributions from Rachel Billinge, Helen Howard, Gabriella Macaro, Rachel Morrison, David Peggie, Ashok Roy, Lesley Stevenson and Nelly von Aderkas, Titian after 1540: Technique and Style in his Later Works, National Gallery Technical Bulletin 36, 2017, pp. 6-39. Catalog: Part 1 pp 64-75. Jacqueline Ridge and Marika Spring, The Conservation History of Titian’s ‘Diana and Actaeon’ and ‘Diana and Callisto’ pp. 116-123 Notes and Bibliography pp. 124-136.

Pigments Used in This Painting

Resources

See the collection of online and offline resources such as books, articles, videos, and websites on Titian in the section ‘Resources on Painters‘

PowerPoint Presentations

Painter in Context: Titian

A richly illustrated presentation on the Venetian Renaissance painter Titian (Tiziano Vecellio) containing information on painting technique, pigments employed, and important written and online resources.

Number of slides: 23

Formats included in the download: PowerPoint Screen Presentation (ppsx) and pdf

Videos

Video: Titian, Diana and Actaeon' by National Gallery London

Video: 'Titian: Love, Desire, Death, by National Gallery London

Publications and Websites

Publications

(1) Jill Dunkerton and Marika Spring. With contributions from Rachel Billinge, Helen Howard, Gabriella Macaro, Rachel Morrison, David Peggie, Ashok Roy, Lesley Stevenson and Nelly von Aderkas, Titian after 1540: Technique and Style in his Later Works, National Gallery Technical Bulletin 36, 2017, pp. 6-39. Catalog: Part 1pp 64-75. Jacqueline Ridge and Marika Spring, The Conservation History of Titian’s ‘Diana and Actaeon’ and ‘Diana and Callisto’ pp. 116-123 Notes and Bibliography pp. 124-136.

(2) Higgins, C., Charlotte Higgins on Titian’s Diana and Actaeon and the forbidden gaze. The Guardian. 21. March 2009, [Accessed 30 Jul. 2017].

(3) White, C., Metamorphosis: Titian 2012, Studio International – Visual Arts, Design and Architecture, 14. January 2013. [Accessed 30 Jul. 2017].

(4) Lawson, James. “Titian’s Diana Pictures: The Passing of an Epoch” Artibus Et Historiae, vol. 25, no. 49, 2004, pp. 49–63. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1483747.

(5) Marie Tanner, Chance and Coincidence in Titian’s Diana and Actaeon, The Art Bulletin 56(4):535 · December 1974

DOI: 10.2307/304930

(6) Irina Jauhiainen, Titian’s Diana and Actaeon and Death of Actaeon as Illustrations of a Sacrifice which Differentiates Human Spirit from Animal Materiality, Philosophy of Art History K1531551.

(7) Tanner, M, Sublime Truth and the Senses: Titian’s Poesi (Studies in Medieval and Early Renaissance Art History), Brepols N.V., 2019

Websites

Titian’s ‘poesie’: The commission, National Gallery London

Website of the National Gallery London, Titian’s ‘Diana and Actaeon’ In-depth research.