Giovani Bellini, The Feast of the Gods

1514-29Giovani Bellini, The Feast of the Gods

1514-29Paintings sorted by Historical period | Painter | Subject matter | Pigments used

The Story of Bellini, The Feast of the Gods

The cast of characters in “The Feast of the Gods”

1 = Satyr, 2 = Silenus, 3 = Infant Bacchus, 4 = Silvanus, 5 = Mercury, 6 = Satyr, 7 = Jupiter, 8 = Nymph with bowl, 9 = Cybele, 10 = Pan, 11 = Neptune, 12 = Nymph with outstretched hand, 13 = Nymph with jar on her head, 14 = Ceres, 15 = Apollo, 16 = Priapus, 17 = Lotis

The story in short

The gods amongst whom are Apollo, Jupiter, Mercury, Bacchus, and Priapus celebrate a party in the woods with satyrs, nymphs, and goddesses. After a time spent drinking and cavorting they get tired and the nymph Lotis falls asleep at the edge of the clearing. Priapus desires her and is about to take advantage of her in her sleep.

Priapus lifting the robe of Lotis

Priapus lifting the robe of Lotis

But in the same moment as he lifts her robe the ass of Silenus starts braying loudly and the nymph awakens and pushes him away. Not only is his adventure spoiled but he also becomes the laughing stock of the Gods (see the original text by Ovid further below).

Silenus and his ass

(1) Plesters, J. The Feast of the Gods: Conservation, Examination, and Interpretation. Studies in the History of Art, 40, 1990, s. 26.

(2) Susan Nalezyty, Giovanni Bellini’s “Feast of the Gods” and Banquets of the Ancient Ritual Calendar, The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 40, No. 3 (Fall, 2009), pp. 745-768

The Original Text by Ovid

The original text in Ovid’s Fasti (1)

“A young ass too is sacrificed to the erect rural guardian,

Priapus, the reason’s shameful, but appropriate to the god.

Greece, you held a festival of ivy-berried Bacchus,

That used to recur at the appointed time, every third winter.

There too came the divinities who worshipped him as Lyaeus,

And whoever else was not averse to jesting,

The Pans and the young Satyrs prone to lust,

And the goddesses of rivers and lonely haunts.

And old Silenus came on a hollow-backed ass,

And crimson Priapus scaring the timid birds with his rod.

Finding a grove suited to sweet entertainment,

They lay down on beds of grass covered with cloths.

Liber offered wine, each had brought a garland,

A stream supplied ample water for the mixing.

There were Naiads too, some with uncombed flowing hair,

Others with their tresses artfully bound.

One attends with tunic tucked high above the knee,

Another shows her breast through her loosened robe:

One bares her shoulder: another trails her hem in the grass,

Their tender feet are not encumbered with shoes.

So some create amorous passion in the Satyrs,

Some in you, Pan, brows wreathed in pine.

You too Silenus, are on fire, insatiable lecher:

Wickedness alone prevents you growing old.

But crimson Priapus, guardian and glory of gardens,

Of them all, was captivated by Lotis:

He desires, and prays, and sighs for her alone,

He signals to her, by nodding, woos her with signs.

But the lovely are disdainful, pride waits on beauty:

She laughed at him, and scorned him with a look.

It was night, and drowsy from the wine,

They lay here and there, overcome by sleep.

Tired from play, Lotis rested on the grassy earth,

Furthest away, under the maple branches.

Her lover stood, and holding his breath, stole

Furtively and silently towards her on tiptoe.

Reaching the snow-white nymph’s secluded bed,

He took care lest the sound of his breath escaped.

Now he balanced on his toes on the grass nearby:

But she was still completely full of sleep.

He rejoiced, and drawing the cover from her feet,

He happily began to have his way with her.

Suddenly Silenus’ ass braying raucously,

Gave an untimely bellow from its jaws.

Terrified the nymph rose, pushed Priapus away,

And, fleeing, gave the alarm to the whole grove.

But the over-expectant god with his rigid member,

Was laughed at by them all, in the moonlight.

The creator of that ruckus paid with his life,

And he’s the sacrifice dear to the Hellespontine god.”

References

(1) Ovid, Fasti, Book 1, translated by A. S. Kline, the website of Poetry in Translation.

The History of the Painting

The history and other aspects of this painting are very lucidly depicted and explained in the website “Investigating the Feast of the Gods” at WebExhibits. It is very worthwhile to peruse all parts of this web exhibit (1).

Bellini’s (and Titian’s) ‘The Feast of Gods‘ was one of the five masterpieces of Italian Renaissance paintings residing in the private gallery of Alfonso d’Este, the Duke of Ferrara. The Camerino d’alabastro (Alabaster Room) in the ducal palace was – without a doubt – one of the most significant art collection projects of its time (1 – 5). With the help and under the influence of his sister, Isabella d’Este, he had commissioned paintings of mythological and bacchanalian subjects with Raphael, Dosso Dossi, Giovanni Bellini and Titian.

The history of ‘The Feast of the Gods’ is rather special and is described on the website of the National Gallery of Art as follows (4):

“The Feast was the first in a series of mythologies, or bacchanals, commissioned by Duke Alfonso d’Este to decorate the camerino d’alabastro(alabaster study) of his castle in Ferrara. Bellini completed it two years before his death in 1514. Years later, the Duke commissioned two reworkings of portions of Bellini’s canvas. Dosso Dossi made an initial alteration to the landscape at left and added the pheasant and bright green foliage to the tree at upper right. Most famously, Bellini’s student, Titian, made a second set of alterations, painting out Dosso’s landscape with the dramatic, mountainous backdrop now seen, leaving only Dosso’s pheasant intact. It is possible that Titian wished to harmonize the Feast with the other, later paintings he also created for the camerino at the Duke’s behest. The figures and elements of the bacchanal were untouched by the later artists and remain Bellini’s own. The original tonalities and intensity of the colors have recently been restored, and the painting has regained its sense of depth and spaciousness.”

The concept and planning for the Camerino d’alabastro had been changed several times (1) and the final arrangement consisted of the following works: Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne, Worship of Venus and Bacchanal of the Andrians, Bellini’s (and Titian’s) Feast of the Gods and the Bacchanals of Men by Dosso Dossi.

Titian, Bacchus and Ariadne, 1523

Titian, The worship of Venus, 1518

Titian, Bacchanal of the Andrians, 1523-24

Giovanni Bellini, The Feast of the Gods, 1514-29

The latter painting by Dossi is possibly lost, although it is sometimes being tentatively identified as the Bacchanal (Feast of Cybele) in the National Gallery in London.

Overview

Medium: Oil

Support: Canvas

Size: 170.2 x 188 cm

Art period: High Renaissance

National Gallery of Art Washington

Widener Collection 1942.9.1

Provenance: Feast of the Gods, Mapping Paintings

Scientific Investigation and Pigment Analysis

Scientific Investigation

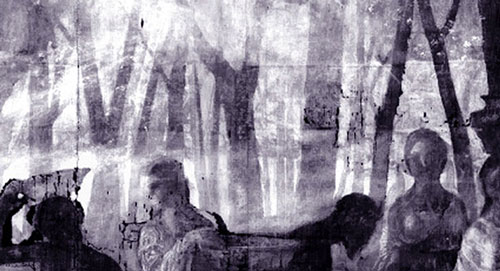

The painting is signed and dated by Bellini in 1514. It was long known that Titian overpainted the background landscape probably in 1529. The first investigation of the painting by Walker (5) in 1956 has shown that the situation is much more complex than this.

The Feast of the Gods underwent a thorough cleaning and conservation procedure at the National Gallery of Art in Washington in 1985 and was extensively investigated by a variety of scientific methods such as infrared reflectography and x-ray radiography (1 – 3). This investigation has been also popularized on the website “Investigating Bellini’s Feast of the Gods” at WebExhibits (4).

First, it was proven that the foreground landscape and the figures in the foreground have not been altered and can be seen in the present version of the painting exactly as Bellini painted them. It came to light, however, that Bellini himself changed the composition slightly, one example being the eroticization of the female figures. The blue dress of the nymph with the jar on her head was originally placed high on her chest. Bellini then overpainted it so that her right breast is exposed in the present version. The original less erotic version can clearly be seen in the detail of the X-radiograph.

The background landscape is posing the most profound questions as regards the history of the painting. The X-radiograph points to several of the open questions.

Bellini, The Feast of the Gods, X-Ray image

Bellini, The Feast of the Gods, X-Ray image

Bellini and Titian, The Feast of the Gods, detail of the present-day version

The most striking feature of the X-radiograph are the tree trunks on the left behind the figures. They are quite similar to the tall trees on the right which are still visible in the present version of the painting. The background landscape in the original version by Bellini thus consisted of a continuous line of high-trunked trees as can still be seen on the right. A similar group of trees in the background can be found in another painting by Bellini.

Giovanni Bellini, The Assassination of St Peter Martyr, ca 1509, The Courtauld Gallery, London

The present landscape with its thick foliage was most probably painted by Titian some 15 years after Bellini completed the painting.

But the X-radiograph revealed another albeit less obvious clue to the secrets of The Feast of the Gods. In the upper left part of the painting, a group of buildings is faintly visible in the X-radiograph.

Further investigation has shown that the original background landscape by Bellini was almost entirely overpainted by an artist tentatively identified as Dosso Dossi, before Titian again overpainted the entire landscape. It has also been shown that Titian left two smaller spots of the Dosso’s landscape untouched so they are still visible in the present version. One of these spots is the pheasant sitting on a branch in the upper right part of the painting.

The website “Investigating Bellini’s Feast of the Gods” shows the images of the three versions of the painting: Bellini’s original, Dosso’s background landscape, and the final Titian’s landscape. The viewer can also look at the painting using an infrared or an X-ray loupe.

References

(1) Plesters, J. The Feast of the Gods: Conservation, Examination, and Interpretation. Studies in the History of Art, 40, 1990.

(2) Plesters, J., Examination of Giovanni Bellini’s Feast of the Gods: A Summary and Interpretation of the Results, Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 45, Symposium Papers XXV: Titian 500 (1993), pp. 374-391

(3) Bull, D., The Feast of the Gods: Conservation and Investigation, Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 45, Symposium Papers XXV: Titian 500 (1993), pp. 366-373

(4) Investigating Bellini’s Feast of the Gods, WebExhibits website.

(5) John Walker, Bellini and Titian at Ferrara: A Study of Styles and Taste, Phaidon Publishers, 1956

Pigment Analysis

‘The Feast of the Gods’ underwent a conservation treatment around 1990 and an extensive pigment analysis was done at the same time (1). This pigment analysis is depicted in a very appealing way on the website of WebExhibits (2). The website shows an animated pigment analysis with the attribution of each pigment layer to the appropriate painter (Bellini, Dosso or Titian). It is highly recommendable.

In order not to duplicate the work of Michael Douma at WebExhibits only the principal pigments of the colourful draperies are shown here.

Blue Draperies

The draperies of infant Bacchus (1), a nymph with the bowl (2), a nymph with the jar on her head (3), and that of Apollo (4) are painted in different mixtures of natural ultramarine and lead white with several layers on top of each other.

1 Infant Bacchus: 1. pale blue layer: lead white with fine particles of ultramarine, 2. deep blue layer: large particles of ultramarine in a matrix of lead white, 3. translucent very thin layer: blue glaze of ultramarine in a translucent medium.

Red Draperies

The draperies of Jupiter (6), Silvanus (5), Cybele (7), Ceres (9), and Neptune (8) are of varying shades of red, crimson, and shades of orange-red.

6 Jupiter: The only important occurrence of vermilion is in the deep red of Jupiter’s cloak. 7 Cybele: 1. layer: red lake and lead white, 2. glaze of purple-crimson color, 3. The top layer contains some granules of lead-tin-yellow. 8 Neptune: red lake pigment in full strength on a pink underpainting layer.

Green Draperies

The robes of Mercury (10) and Neptune (11) are green, the tunic of Priapus (12) is red and green.

10 Mercury and 11 Neptune: The draperies are painted in a mixture of lead-tin-yellow with malachite and/or verdigris with a glaze of copper resinate. 12 Priapus: similar pigments as in 10 and 11 with highlights in a thin opaque layer (scumble) of vermilion.

Yellow and Orange Draperies

The robes of Silenus (13), Apollo (15) and the nymph (14) are varying shades of orange and yellow.

13 Silenus: The robe is painted in a mixture of orpiment and realgar. 14 Nymph: lead-tin-yellow and lead white with some vermilion in the shadows. 15 Apollo: essentially realgar with some purplish-red lake.

References

(1) Plesters, J. The Feast of the Gods: Conservation, Examination, and Interpretation. Studies in the History of Art, 40, 1990, s. 53.

(2) Investigating Bellini’s Feast of the Gods, Pigments, WebExhibits website.

Pigments Used in This Painting

Resources

PowerPoint Presentations

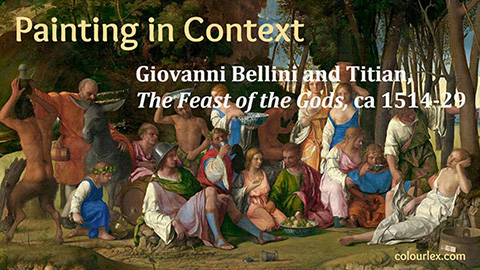

Painting in Context: Giovanni Bellini, The Feast of the Gods

A richly illustrated presentation on one the best investigated and most interesting late Renaissance paintings containing information on the history of the painting itself, its scientific investigation, pigments employed, and important written and online resources.

Number of slides: 17

Formats included in the download: PowerPoint Screen Presentation (ppsx) and pdf

Videos

Video: 'Giovanni Bellini, The Feast of the Gods' by Blulight Gallery

Video: 'Giovanni Bellini, The Feast of the Gods' by Smarthistory

Publications and Websites

Publications

(1) Plesters, J. The Feast of the Gods: Conservation, Examination, and Interpretation. Studies in the History of Art, 40, 1990.

(2) Plesters, J., Examination of Giovanni Bellini’s Feast of the Gods: A Summary and Interpretation of the Results, Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 45, Symposium Papers XXV: Titian 500 (1993), pp. 374-391

(3) Bull, D., The Feast of the Gods: Conservation and Investigation, Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 45, Symposium Papers XXV: Titian 500 (1993), pp. 366-373

(4) Anderson, Jaynie. “The Provenance of Bellini’s Feast of the Gods and a New/Old Interpretation.” Studies in the History of Art 45 1993, 264-287

(5) Susan Nalezyty, Giovanni Bellini’s “Feast of the Gods” and Banquets of the Ancient Ritual Calendar, The Sixteenth Century Journal, Vol. 40, No. 3 (Fall, 2009), pp. 745-768

(6) Wind, E., Bellini’s Feast of the gods: a study in Venetian humanism, Harvard Univ. Press, 1948.

(7) Charles Hope, The ‘Camerini d’Alabastro’ of Alfonso d’Este-I, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 113, No. 824 (Nov. 1971), pp. 641-647+649-650

(8) Charles Hope, The ‘Camerini d’Alabastro’ of Alfonso d’Este-II, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 113, No. 825, Venetian Painting (Dec. 1971), pp. 712+714-719+721

(9) John Walker, Bellini and Titian at Ferrara: A Study of Styles and Taste, Phaidon Publishers, 1956

(10) Manca, Joseph. “What is Ferrarese about Bellini’s Feast of the Gods?” Studies in the History of Art 45 1993, pp 300-313

(11) Anthony Colantuono, Dies Alcyoniae: The Invention of Bellini’s Feast of the Gods, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 73, No. 2 (June 1991), pp. 237-256

(12) Brown, D. A., The Pentimenti in The Feast of the Gods, Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 45, Symposium Papers XXV: Titian 500 (1993), pp. 288-299

Websites

Investigating Bellini’s Feast of the Gods, WebExhibits website